Record numbers of greater white-fronted geese (Anser albifrons) at Goose Pond

Greater white-fronted goose, photo by Ryan Askren

Greater white-fronted geese (aka specklebelly) can be identified by their light belly with black checkers, streaks or blotches and orange legs. They are named for the white patch of feathers bordering the base of the bill, and the latin name albifrons is derived from albus meaning white and frons meaning forehead. At a distance they are difficult to pick apart from Canada geese, but they’re smaller, have a more rapid wing beat, and announce themselves with energetic squeaks (listen in here). This opportunistic species has a nearly circumpolar arctic distribution and in North America, white-fronted geese are distinguished by a Pacific and Midcontinental population.

Families Stick Together

Adults arrive at the breeding grounds of Alaska and Canada in May. They select a pond, shallow lake, or stream shoreline with an abundance of sedges or moss on which the nest is built. So far they sound similar to other nesting geese of the north like snow geese and brant, right? There are a lot of differences, but this is one that I found particularly interesting.

Family pair bonds last longer in white-fronts than other geese, and broods frequently stay with their parents for a multiple years. Pretend that a breeding pair successfully reared three young in 2019. Those three young are probably still with the parents. When the family group arrives back on the breeding ground in 2020, the three young from 2019 are likely to help defend their parents nest from predators and conspecifics, possibly throughout the breeding season. White-front aren’t sexually mature until they are two or three years old so in this situation, the young from 2019 will not compete for their parents' breeding territory in 2020.

Satellite image of the Alaskan landscape preferred by white-fronted geese

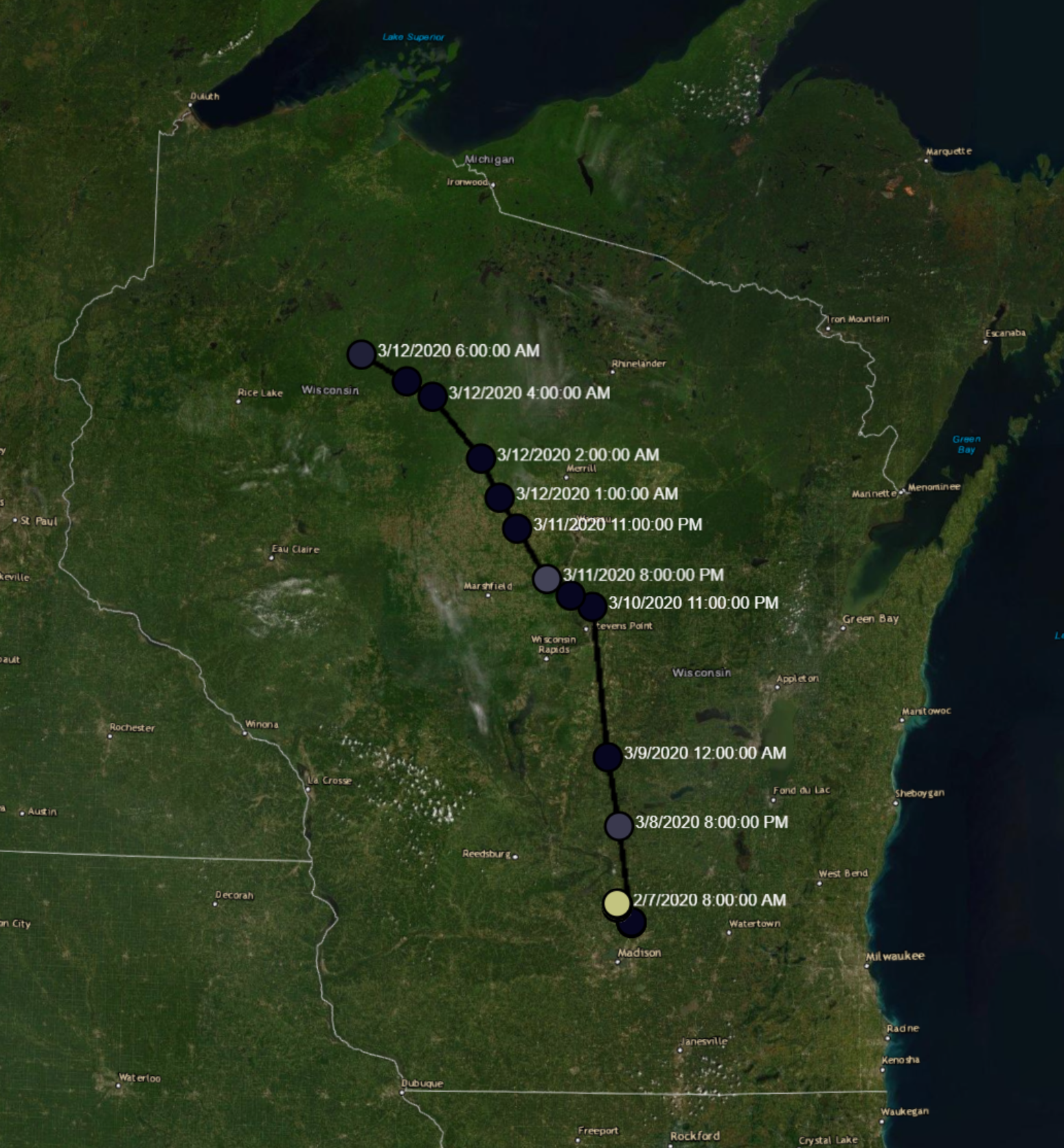

Migration Changes in Wisconsin

Check out this great animated map, which tracks the spring and fall migration of greater white-fronted geese.

On their southward journey, white-fronted geese typically make two major hops. The first is from the arctic to grain fields in Saskatchewan and Alberta (about 1,400 miles), and then make another major move to the gulf coast and Mississippi Alluvial Valley (about 1,800 miles). They winter as far south as subtropical settings on the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico. White-fronted geese take a much more leisurely approach to spring migration, and they utilize diverse habitats from deserts and grasslands to river deltas and major agricultural areas.

White-fronted geese in flight, notice the variation in the coloring in the bellies. Photo by Arlene Koziol

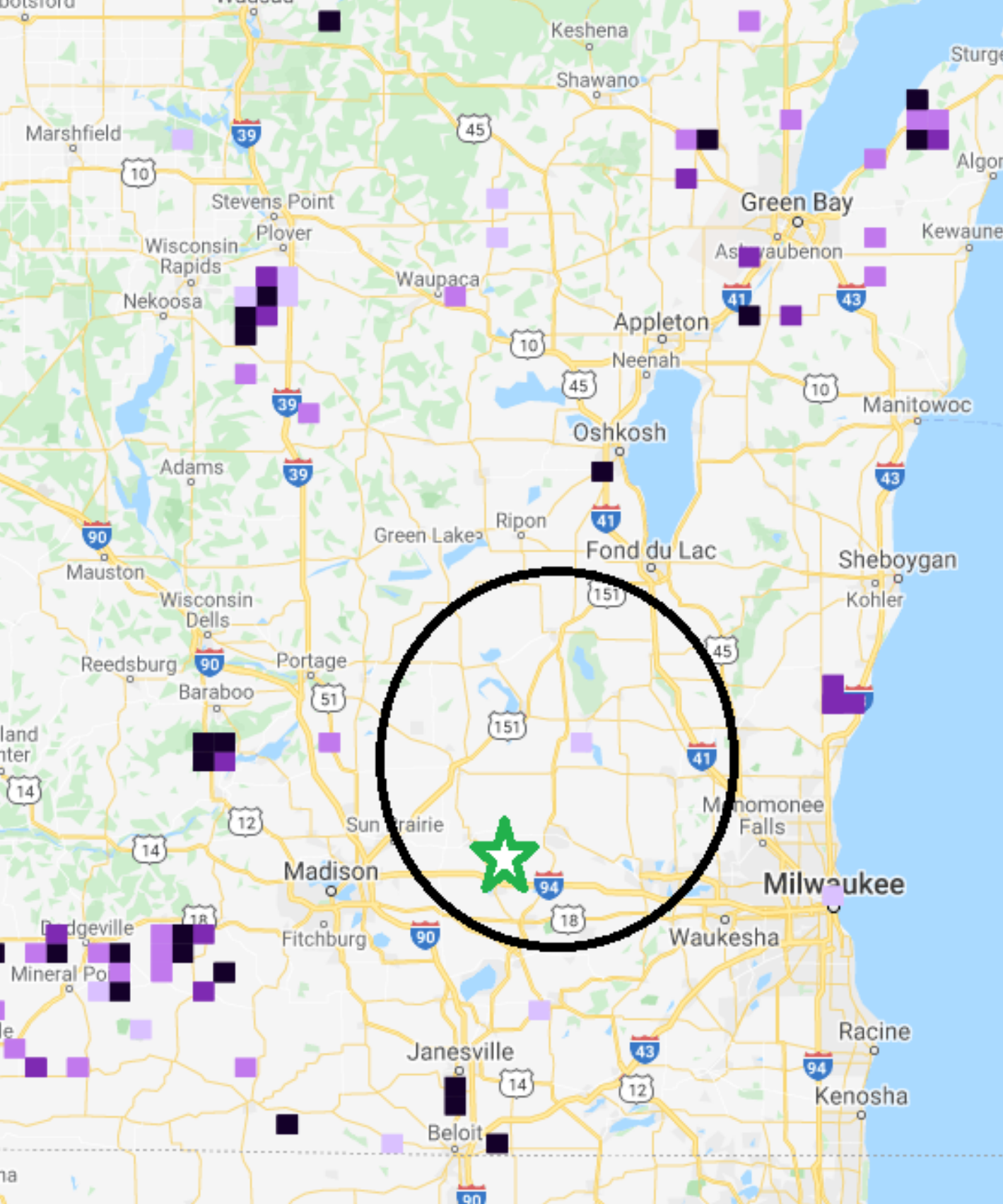

According to Samuel Robbins Wisconsin Birdlife, white-fronted geese had “large numbers in spring and fall” or were even described as “an abundant migrant” in Wisconsin prior to 1890. Their populations in Wisconsin declined dramatically over the next two decades, and only a single observation of white-fronts was published between 1910 and 1938. While there were increasing observations after 1940, the 1990s in particular set the stage for a dramatic shift. This is where Columbia County comes in. Below is a short history of observations of white-fronted geese in Wisconsin provided by the Passenger Pigeon which is published by The Wisconsin Society for Ornithology.

1995 - Three counties. “Daryl Tessen had 13 in Outagamie County on 12 March and Bill Hilsenhoff had 17 in Dane County on 19 March.”

2003 - Ten counties. “The characterization of this species in Robbins Wisconsin Birdlife (1991) as a rare species reads like ancient history, with double-digit flocks now routine…Tessen was able to estimate well over 1,000 birds in Columbia and Dane Counties (combined) on March 29.”

2004 - 11 counties. “Numbers that would have been jaw-dropping even ten years ago peaked at 1,350 in Columbia County on March 20 (Tessen).”

2008 - “The big numbers were in Columbia, Lafayette, and Dane Counties, peaking at 475 individuals in Columbia County on 13 April (Prestby).”

2012 - “By 8 March Tessen had already tallied the season’s high count with his report of 1,000 birds in Columbia County.”

2014 - “On that same date (2 April) numbers in Columbia County increased significantly with 750 birds tallied in the ephemeral flooded fields on Wangsness Road.” Wangsness Road is four miles southwest of Goose Pond.

2017 - “Reported in 46 counties across the state this season...High count of 1,000 observed in Dane County at Island Lake WPA (David Johnson) on March 17, 2017, and in Jefferson County at Hope Lake (Aaron Stutz) on March 12, 2017.”

2018 - “Reported in 36 counties across the state this season...High count of 2,600 observed in Columbia County (Ted Keyel) on 17 March.”

2020 - (From WisBird) “More large numbers of White-fronted Geese were seen in several Columbia County ponds totaling about 3,000 - 4,000.

Photo by Arlene Koziol

It is clear that white-fronted geese are gaining ground in Wisconsin, particularly Columbia County, but why is their migration shifting? The first reason is increasing populations. White-front numbers have been on a steady rise for decades. As more individuals inhabit a region, they tend to spread out to reduce competitive pressures related to food resources. The second reason probably has to do with a change in their wintering grounds. Geese love rice. Texas was the undisputed rice center of the United States until the 1970s. Around that time, drought and global competition reduced the amount of rice grown in Texas. Mississippi Alluvial Valley states like Arkansas were able to capitalize on this change by converting row crops like corn and beans into rice fields where they could utilize their wetter climate and more abundant water resources. White-fronted geese seem to have shifted both their primary wintering grounds and spring migration routes much farther to the east in step with agricultural changes.

The winter population moved northeast and large numbers now winter south of Wisconsin so when they move north, they find Wisconsin including Columbia County with a large acreage of open water and abundant picked cornfields to feed in. Similar to other long-lived waterfowl species, it is likely that they remember ideal habitats and return to those local areas in subsequent years.

Graphic shows changes in winter distribution of greater white-fronted geese between 1975-2015. Graphic provided by Ducks Unlimited

Record Numbers at Goose Pond

The first time white-fronted geese were seen at Goose Pond was on March 26, 1978 by Laura Erickson. On March 22nd, 1980, Mark and Sue counted six individuals and Randy Hoffman spotted two more. The high counts for each decade at Goose Pond are 50 in the 1980’s, 10 in the 1990s, 50 in the 2000s, and 1,850 in the 2010s. The record has already been broken twice during this 2020 spring migration. Calla Norris and I counted 1,972 white-fronts on March 16, and Tom and Wendy Schultz counted 2,200 just five days later. According to past records, we’re at peak migration time for white-fronts here at Goose Pond. We encourage you to visit and view these charismatic creatures before their numbers dwindle significantly by mid-April. If you can’t make it in person, check out Arlene Koziol’s wonderful collection of Goose Pond photos taken this week.

A lot of greater white-fronted geese at Goose Pond! Photo by Arlene Koziol

Additional Fun Facts

White-fronts often mob terrestrial predators by advancing on a predator as a threatening flock unless they are undergoing wing molt.

A high degree of natal philopatry and tendency to pair with genetically similar mates means there is strong likelihood of population structuring and the existence of unique genotypes. It is important to identify and protect these distinct groups.

The oldest recorded greater white-fronted goose was at least 25 years, 6 months old when it was found in Louisiana in 1998. It had been banded in Nunavut in 1975. A female in captivity lived to be a staggering 46 or 47 years old!

Written by Graham Steinhauer, Goose Pond Sanctuary land steward