Forty-one years ago when Mark and Sue moved to Goose Pond, there were only paper records of bird observations by “regular birders” and observations recorded in our personal journals. Today we are very fortunate to work at the computer where we check out Wisconsin eBird reports that are updated immediately, that include a “hotspot” for Goose Pond Sanctuary observations. We explored 2019 Wisconsin eBird observations for Goose Pond and examined our journal entries from November - December 11 for 1979.

Goose Pond, 2017, photo by Arlene Koziol

Then: Journal Entries from November - December 11, 1979

In 1979 Madison Audubon only owned 100 acres at Goose Pond that included the west pond and very little upland cover. Hunters hunted for pheasants along the railroad tracks and frequently shot adjacent to boundary mostly for waterfowl. Before freeze up on November 30th, the high count that month was only 50 Canada geese and 42 tundra swans. Geese and swans required larger refuge areas than mallards that could fly in high and land in the middle of the pond. Sue and Mark counted 4,925 mallards on November 9th returning to Goose Pond the last hour of daylight!

Other interesting entries include:

an observation of nine gray partridge (Hungarian partridge or huns) along Goose Pond Road. The last huns were seen in 2000.

On November 28 when the pond was almost frozen, Mark picked up a dead tundra swan that was frozen in the ice and shot a hen mallard that was walking around in tight circles. Lab results did not confirm any disease problems with both birds.

We also learned that month that an old squaw (a long-tailed duck) was seen by Bill Smith and Frank Freese the last week of October.

Now: Field Observations and Reports from eBird, 2019

In October of 2019 we received 6.5 inches of snow that forced many birds to migrate south. Goose Pond froze over November 12 following record lows of 1 degree on November 8 and 12. However, highs were in the 40s by the 16th and the pond reopened. The pond finally froze over for a second time on Dececember 10.

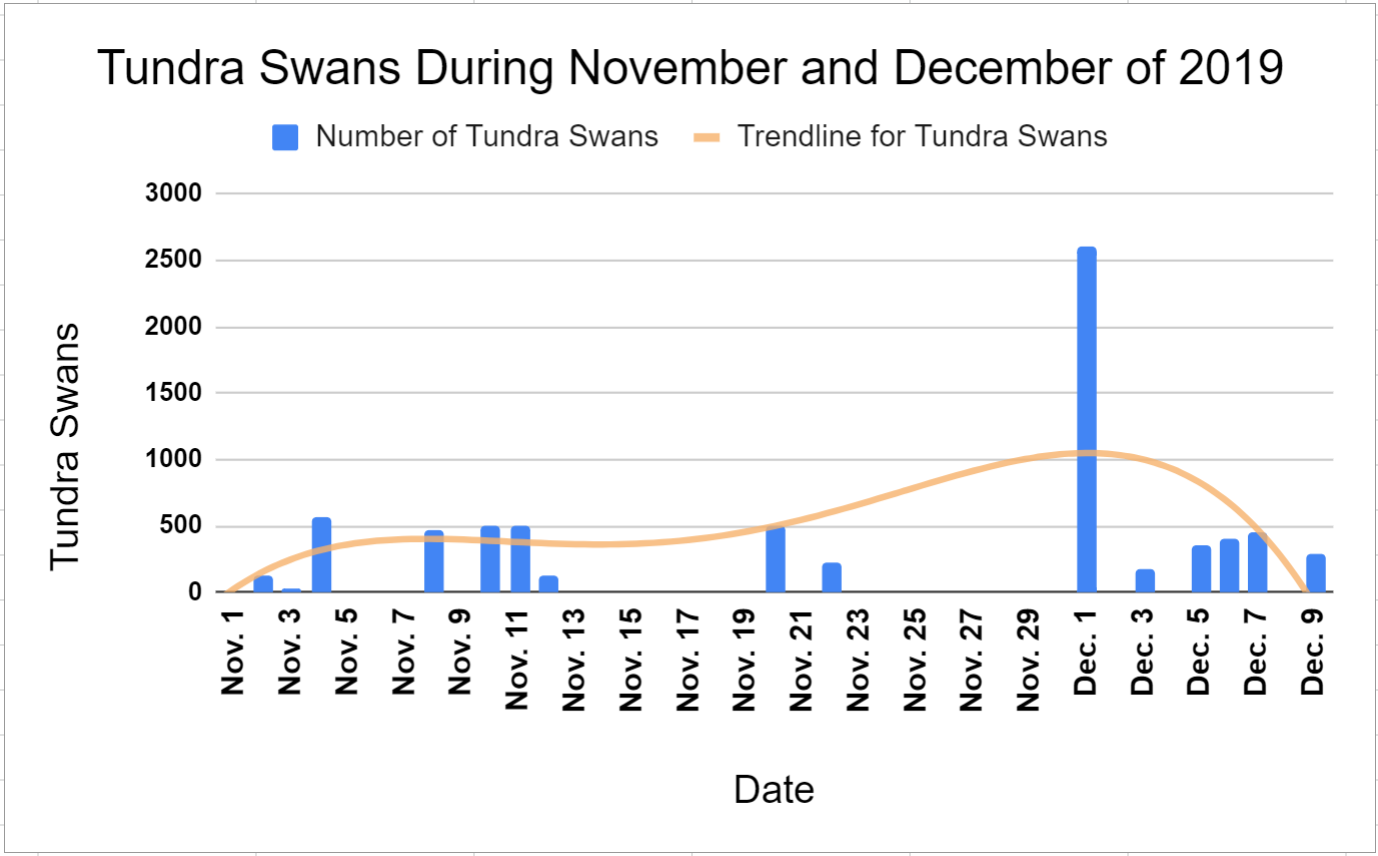

Thirty-five bird watchers submitted 38 Wisconsin eBird checklists for 25 days from November 1 to December 11. In total, the birders reported 54 species and JD Arnston and the three of us recorded high counts for tundra swans (2,600), mallards (12,500) and sandhill cranes (733). Most visitors birded from Prairie Lane or Goose Pond Road and concentrated on waterbirds. Some birders commented that there were “thousands of birds” or “too many to count”.

A pond bursting with life! Photo by Monica Hall, December 2019

The 54 species reported are (species also seen in 1979 are in bold): snow goose, Ross’s goose, greater white-fronted goose, cackling goose, Canada goose (high of 3,800), mute swan (1 and uncommon in Wisconsin), trumpeter swan (high of 8), tundra swan (record count on Dec. 2), blue-winged teal (late observation of 3 on Nov. 3), northern shoveler, gadwall, American wigeon, mallard (record count on Dec. 1), American black duck (high of 22 but probably many more in mixed in with the mallards on Dec. 1), northern pintail, green-winged teal, canvasback (60 on Nov. 3), redhead (45 on Nov. 3), ring-necked duck (150 on Nov. 3), lesser scaup (35 on Nov. 3), bufflehead, common goldeneye (20 on Nov. 9), hooded merganser, common merganser, ruddy duck (40 on Nov. 3), ring-necked pheasant, pied-billed grebe, horned grebe (very good find on Nov. 1), rock pigeon, mourning dove, American coot (122 on Nov. 1), sandhill crane (record count of 733 in migration on Dec. 2), ring-billed gull (142 on Nov. 26), great blue heron, great egret (late record of 1 on Nov. 9), northern harrier, bald eagle (reported 1 or 2 adults on 10 days), red-tailed hawk, American kestrel, northern shrike (Dec. 5), blue jay, American crow (91 on Nov. 9), horned lark, European starling, American robin (3 on Nov. 13), American pipit (22 on Nov. 1), house finch, American goldfinch, Lapland longspur, snow bunting, American tree sparrow, dark-eyed junco, red-winged blackbird (21 on Nov. 5), and northern cardinal.

Swan counts at Goose Pond, November and December 2019, graph by Graham Steinhauer

In early December 2019, we wrote about having “tons” of waterfowl on the pond. Here are our tabulations: 2,600 tundra swans @ 15 pounds each = 19.6 tons, 3,800 Canada geese @ 8.6 pounds each = 16.3 tons, 12,500 mallards @ 2.2 pounds each = 13.8 tons, and 733 sandhill cranes were seen in migration heading southeast - 733 @ 9.5 pounds each = 3.5 tons. Grand total = 53 tons of wetland birds!

The snowy owl reported in Columbia County, December 2019. Photo by Arlene Koziol

In addition, if you check out recent Wisconsin eBird sightings you will notice that Graham reported with a photo of a snowy owl near UW - Arlington Research Farms. Thanks to the their staff for calling us about the owl.

We and many others also report observations to Wisconsin Birding Network - wisbirdn@freelists.org. The American Birding Association catalogs birding related news on the easy to use website. You can submit sightings, take bird quizzes, and see what’s happening in Wisconsin and other states by visiting this website. You can also subscribe to their email list by following the link above, and clicking on “How do I subscribe to a list?”

Written by Mark Martin and Susan Foote-Martin, Goose Pond Sanctuary resident managers, and Graham Steinhauer, land steward