It sounds simple, doesn’t it? You know how to count, so just … well … count them! But as I’m sure any birder—new or experienced—knows, counting birds can be deceptively hard. Not only might you encounter birds in large numbers that may feel overwhelming to parse, but the conditions that you’re viewing birds in are always changing.

Are they flying away from you, much faster than you’d like? Yep. Are they all crowded together in one massive flock on the water, likely obscuring a bunch of other birds in the process? Yup. Is there a bunch of species all jumbled together, making it seemingly impossible to figure out counts for all of them? You betcha.

Not all counts are hard. Sometimes the birds will line up for you in perfect formation, like these five sandhill cranes. Photo by Caitlyn Schuchhardt

When I first started birding, these “hard-to-count” situations were intimidating and not very fun. I love to look at waterfowl on lakes in the fall, but I’d find myself feeling stressed thinking about how on earth I was supposed to count or sort through a massive flock of birds for my checklist, when I really just wanted to spend my time enjoying good looks at the birds.

With practice and the help of some useful estimation methods, counting birds gets easier in time. This week’s Entryway to Birding blog brings you some tips and advice for navigating some of those more challenging, less straightforward counting situations, so you can spend more time enjoying the birds and less time stressing about getting “exact” counts for your checklist.

Now is the time to practice your counting skills—fall migration is picking up, birds are flocking in larger numbers, and waterfowl season is just around the corner. Let’s get started!

Why Count Birds

My eBird list, mid-birding session. One of my favorite things about using eBird is knowing that my sightings can contribute valuable data that researchers and scientists can use to improve bird conservation efforts. You should give it a try! Photo by Caitlyn Schuchhardt

Birding, as a hobby, has a very list-focused bent to it. It’s natural to go out on a bird walk and make a list of the birds you see, whether for your own personal satisfaction or for sharing on eBird. If this isn’t how you bird, that’s fine—the joy of this hobby is that you can participate in it in ways that work best for you. If you’re out simply to observe birds and not count them, feel free to do your thing—but today’s blog post may not be as useful for you.

For those of you interested in counting birds and documenting your sightings, you’re probably familiar with eBird, a citizen science platform where your bird sightings are recorded and available for scientists all over the world to use as they study everything from bird density, to conservation, to the effects of climate change. Maybe you’re already contributing regularly to eBird! That’s awesome. But maybe you’re hesitant and feeling unprepared to contribute, especially if you’re not confident in your bird counting skills.

That’s totally normal. My hope is that today’s post will help you feel a little more confident in your counting skills and to get you accustomed to the art of an educated guess. Precise data, when we can provide it, is great. But that’s not often what we’re faced with when out birding in the field. eBird isn’t expecting your counts to be 100% on the mark, so don’t let any fears of inaccuracy hold you back from contributing your lists.

University Bay, near the Lakeshore Nature Preserve at UW-Madison, is a hotspot for mixed flocks of migrating waterfowl. They often gather in rafts near the shoreline for nice viewing conditions. Counting through a mixed flock can be hard at first—especially when you’re new to IDing birds in the first place!—but it gets easier with practice. Photo by Brandyn Kerscher

eBird has a bunch of resources and advice to help you with counting. These two articles—Counting 101 and the slightly more advanced Counting 201—are must-reads for any eBirder. Much of what I’m sharing today is mentioned in these articles too, but eBird has got some better and more thorough examples. Their articles will also help you better understand how your counting data is meaningful to scientists, so give ‘em a read! You won’t regret it.

Counting Methods

How you count birds is going to be dependent on the conditions of your birding. Are you in the woods, likely running across one or a few birds at a time? Are you on the edge of a lake, scanning a mixed flock of waterfowl? Are you standing in awe of a massive flock of blackbirds that seemed to erupt out of nowhere? Each of these situations calls for a different counting technique.

Counting birds individually

How many great egrets are hiding in this photo? Even when you can count one-by-one, sometimes the scenery can make it a challenge by obscuring birds. (There are 10, by the way!) Photo by Caitlyn Schuchhardt

When you’re out walking around looking for birds, you’ll likely run across several different species as you go. In this situation, keeping a running tally of those individual birds is pretty straightforward. Two cardinals are chillin’ in that bush, and you see another one flying later on your walk, for three cardinals. You keep a running total of each species as you go, and at the end of your walk you have a full list of the birds that you saw in that area. Easy-peasy.

What’s important here is that you keep a running tally as you bird. Don’t head home and try to “recreate” your list later—I guarantee you’ll misremember what you actually saw. Maybe you’re out there with a pencil and notepad, tallying up species as you find them, or maybe you’re using the eBird app on your mobile phone to build your checklist. (Haven’t checked out eBird mobile yet? Take a look at one of our earlier blogs about how to use eBird mobile while out birding.)

Personally, I will take little pit stops every 10-15 minutes while birding to update my eBird checklist. This keeps me from pulling out my phone constantly but also means that the birds I’ve seen are still fresh in my mind.

Counting by 5’s, 10’s, 20’s, 100’s …

Sometimes you don’t encounter just one or two birds at a time, but several or even hundreds—more than you may be able to easily count one-by-one. If you’ve got a large flock flying overhead, they could be out of sight before you have a chance to finish. And if you’ve got a large raft of birds on the water, the angle you’re viewing them at may obscure the birds further back, making counting one-by-one a challenge.

If you’ve got a good idea of what a group of 10 American white pelicans looks like, you might be able to take scan this overhead flock and estimate that there are about 20 birds. You’d be pretty close—there are 21! If you have time and the birds are circling slowly enough, practice! Estimate a guess first, then count them one by one and see how close you were. This is a great way to refine your skills. Photo by Caitlyn Schuchhardt

In this situation, try counting them in increments. Maybe you count 5 or 10 birds to “get a feel” for what that amount looks like, and use that to extrapolate a count for the rest of the group. For larger groups, your increments might get larger too, and you may be counting by 50s or 100s.

Your end total won’t be exact, but it will be a good approximation—and it will be better than no guess at all! You might even find yourself surprised at how many more birds were present than you might have initially thought. When you encounter large flocks, it’s easy to underestimate. Take a look at this photo below of a flock of red-winged blackbirds in a tree. Can you believe that there are 150 birds to the right of the red line?

Expert birder and editor of Birding magazine, Ted Floyd, posted this image to the eBird Community Discussion group on Facebook with this caption: “How many blackbirds are in this tree? 500? Now consider that there are 150 to the right of the vertical red line, the part of the tree with the lowest density of blackbirds. Just another reminder that flocks are often larger than we appreciate!” Photo from eBird Community Discussion Facebook group

If you want to and are able—if conditions allow—you should try for as precise of a count as possible. It’s really helpful to have those exact counts, but don’t feel like you’re required to do this in order for your list to be useful. Your careful estimates are still useful—and encouraged—by eBird!

Counting Birds by Flock Composition

What happens when the massive flock you’re looking at isn’t all one species? There’s a couple things you can do—in whatever order feels natural to you. I’ll generally get started by figuring out what exactly I’m looking at, so I have a list of all the species that are present.

There’s a lot of black and white in this scene, but it’s not all the same species—we’ve got American coots, bufflehead, a Canada goose, a ring-billed gull, and a ruddy duck. Coots seem to make up the most of this group. This may be small enough to count each bird, but imagine if this was a larger flock. What percentage of this image do you think the American coots would make up? Photo by Brandyn Kerscher

Once I know what’s out there in that mix, I’ll count the whole group in increments. In my initial scan of all the bird species present, I may have noticed if there was a species that made up most of the flock. If not, I’ll take another look and figure out the species that seems to be the most numerous. Then I’ll think. Do they seem to make up 50% of the flock? 25% 80%? Whatever the answer is, I’ll use that ratio to estimate a count based on the size of the whole flock, and start “filling in” the other species from there, until I’ve counted 100% of the flock.

Best Practices—Counting Do’s and Don’ts

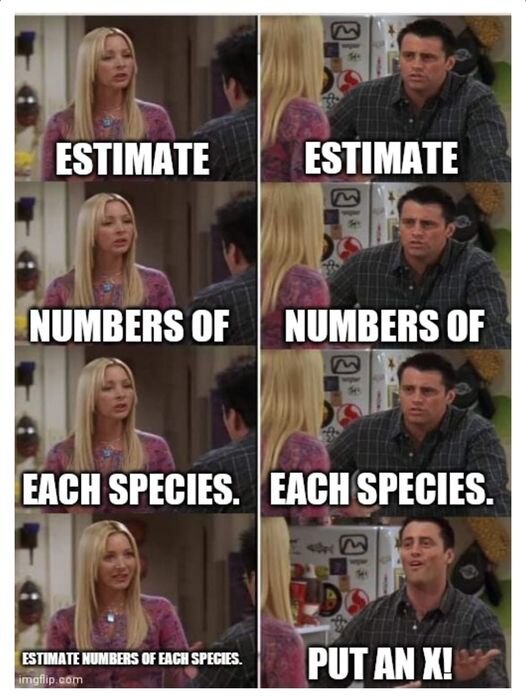

When you’re new to eBird, estimating can feel kinda sacrilegious. But your estimate is much for useful to eBird than a simple X, and you want your data to be useful! So repeat after this meme: “Estimate numbers of each species!” and don’t just put an X. Photo from Birding Memes on Facebook

Your best guess is better than using X. While eBird does offer you the option of putting X to mark that a bird was present, they do discourage using this unless it absolutely can’t be avoided. Your best guess—even if it’s just a gut-feeling guess—is better than a simple X. This is because X could denote just one bird or one thousand birds. eBird has no way of knowing what you saw, unless you give them your best guess.

Don’t count the same bird more than once. When you’re out on a trail and run across a red-bellied woodpecker pecking away at a tree, then see another red-bellied woodpecker in that same area on your way back to the trailhead, you should probably assume it’s the same bird. This is especially important if you’re doing an out-and-back hike—you don’t want to document birds you likely already recorded.

Be conservative in your estimates, but take into account conditions that might influence your count to be higher than it appears. Are the birds tightly packed in a flock, with some birds maybe obscuring others? Is this a large, 3D-group of birds in constant motion? Just like it’s easy to underestimate in certain conditions, it’s also easy to overestimate in others. When in doubt, eBird wants you to be more conservative in your estimate.

Sleeping tundra swans will be a common sight for birders this fall and winter, but their positioning often poses a challenge—it’s hard to see how many swans might be obscured in the back. That’s a factor you should think about as you make your estimate, but still estimate within reason—there’s likely not an additional hundred swans being obscured in this image, but there may be 10-15 we aren’t seeing. Photo by Brandyn Kerscher

Watch out for what eBird calls “false precision” and don’t add actual counts to previous estimates. If you estimate there are roughly 100 tundra swans sleeping in the image above, then later see three more tundra swans fly in and add them to your list, your end total would look like 103 tundra swans. But eBird doesn’t know you estimated the first 100 and thus your very specific-sounding count of “103” implies that you actually counted all those tundra swans, when you really didn’t. If you’re estimating, keep your counts “rounded” to something that ends in 0 or 5. In this situation, you could leave your count at 100 or bump it to 105. (If you had actually counted the birds and ended with a perfect 100, feel free to include a comment that says “actual count” so scientists know you aren’t estimating.)

Resources to Practice, Practice, Practice

The more you practice counting, the better you’ll get. I remember being on group birds walks (in those pre-pandemic days) and seeing more experienced birders look at a flyover flock of Canada geese and, within what felt like less than half a second, declare a confident “32.” I’d still be frantically counting one-by-one, and sure enough, end up with 32. How did they do it so fast?!

Practice. The more you test your bird counting skills, the more refined they’ll get. You’ll find that in time, even your gut-instinct or intuition will start to get more and more accurate. Here are some resources to help you improve your educated guessing!

With some practice, you’ll be firing off estimates for huge flocks like nobody’s business. Give this one your best guess—how many ring-billed gulls is this?! (Your guess is as good as mine—and is better than just an X!) Photo by Brandyn Kerscher

This webpage was created by Martin Reid, an experienced birder from Texas, and it offers a fun way to “test” your counting intuition by looking at some real-life birding scenarios. Look at each photo, but do not attempt to actually count the birds—just give your best estimate. After you’ve guessed, click on the photo again. A dot will show over each bird and you’ll see an exact count appear on the image. How close were you?

David Sibley’s website has some fun counting quizzes that you can practice. They are a little different than the previous website, since they don’t use actual birds, but rather lentils … but you’d be surprised at how well those little legumes evoke bird flocks!

This time last year, I was just getting started with birding and fall migration was picking up. I remember going to places like University Bay or Upper Mud Lake and seeing huge flocks of migrating waterfowl—many birds that I hadn’t actually seen before (or at least, hadn’t paid attention to in my pre-birding days). I loved to just watch birds on the water and enjoy them as they dove or dabbled or interacted with each other.

Greater white-fronted geese were a new fall favorite of mine. This photo wasn’t taken in fall, but does show off how gorgeous these “specklebellies” are. The Madison area will see greater white-fronted geese migrate through with other waterfowl upcoming this fall, so keep your eyes peeled and be ready to count ‘em! Photo by Brandyn Kerscher

But then it would come time to make my eBird checklist and I would get so flustered because there were so many birds! I hadn’t been really paying attention to how many of each so then I’d try and count them one-by-one … but they were moving around so much, some flying in and out, some diving out of sight. And suddenly it’d be an hour later, and I’d be tired and cold and hungry and kinda miserable.

Don’t let counting birds suck the fun out of birding. Don’t let it hold you back from using eBird. Get comfortable with estimating when it’s needed, and you’ll find yourself a happier birder—able to enjoy the wonder and beauty of what’s in front of you and able to make your sightings count in the grand world of citizen science.

That’s all for this week! Happy birding (and counting!) and I’ll see you next week.

____

Caitlyn is the Communications and Outreach Assistant at Madison Audubon. She’s crazy for birds because they changed her life. She’ll be back next Monday with some tips and tools for birders, new and experienced! Between now and then, she’d love to hear about the birds you’re seeing and hearing. Leave a comment below or email to drop her a line!