Columbia, the snowy owl, looks at the camera with her sharp, yellow eyes. Photo by Monica Hall

Update on “Columbia”

You can learn more about her by checking out her first Friday Feathered Feature. https://madisonaudubon.org/fff/2020/1/31/we-named-her-columbia

Scott Weidensaul’s March 1st Project SNOWstorm blog post is titled Zugunruhe to You, Too! https://www.projectsnowstorm.org/posts/zugunruhe-to-you-too/

“Ornithologists use the German term, zugunruhe — which translates to “migratory restlessness” — to describe this kind of growing itch that migrants feel as the seasons change. It’s brought on by hormonal changes triggered by both the bird’s internal circadian rhythms and the changing day length. Often it’s a strong wind from the right direction — southerly, in this case — that prompts an exploratory flight…” Four snowy owls with transmitters in the Dakotas and Saskatchewan exhibited zugunruhe the last week of February. Scott wrote, “There’s been less evidence of zugunruhe in the owls farther east. In Wisconsin, Columbia has been tracing a very distinct movement pattern northeast of Morrisonville, a narrow, 7.5-mile (12-km) long path anchored at one end by the farmland and a sand quarry near Audubon’s Goose Pond Sanctuary, and at the other what must be a highly productive field for hunting just east of a large housing development.”

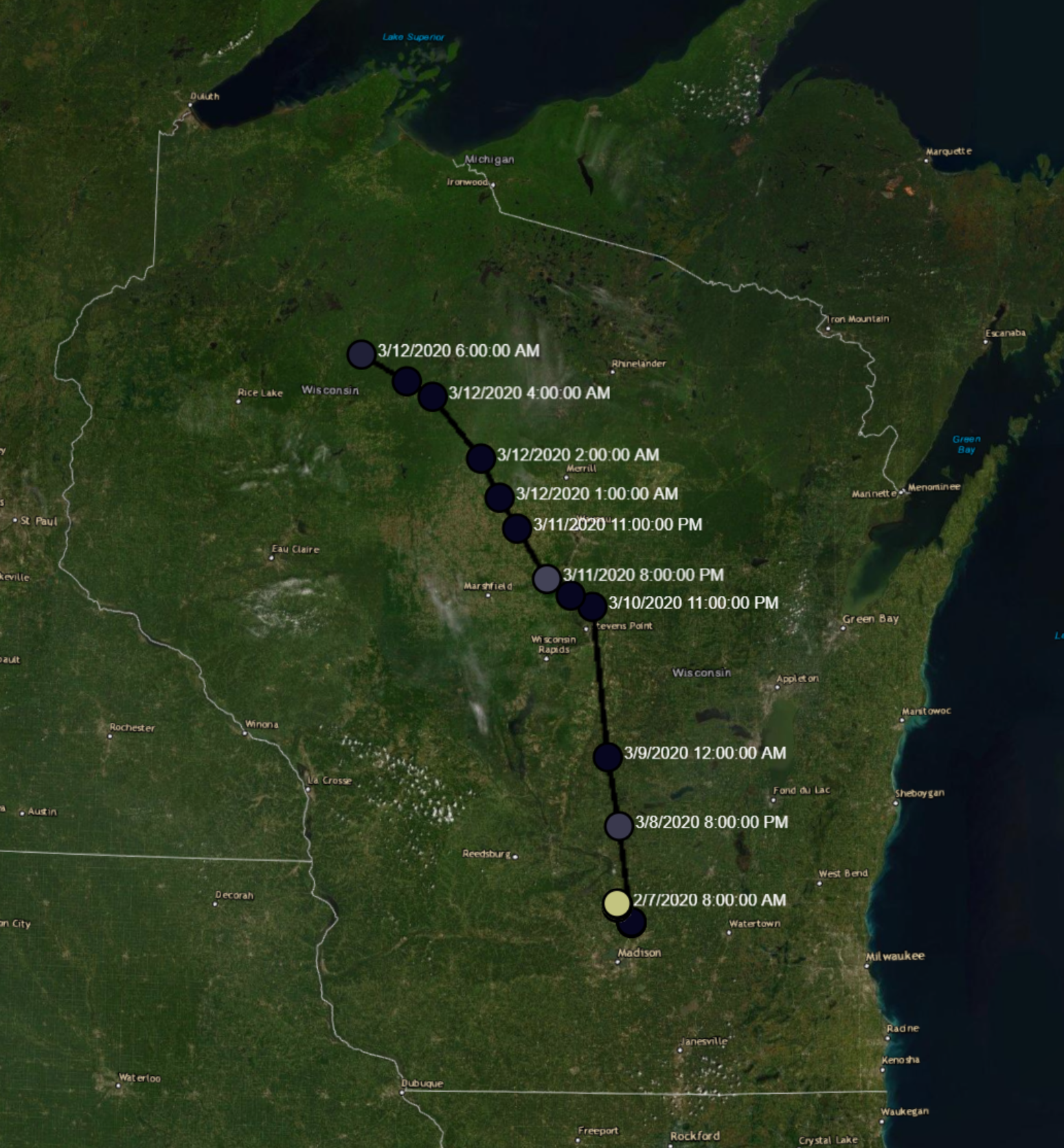

Columbia did not exhibit any zugunruhe until March 8th. At sunset she said goodbye to her new friends and headed north. She was flying at 30 miles per hour on southerly 12 mile per hour winds when she passed South Leeds. At one location she was clocked at 41 miles per hour.

A path marks Columbia’s northward journey since March 8.

Columbia would make frequent stops, with her first at the French Creek North State Natural Area in southern Marquette County. She then headed over John Muir County Park (this location was on her bucket list), and ended up that morning just south of the Plainfield Tunnel Channel Lakes State Natural Area in Waushara County, 62 miles from her start 12 hours before. She roosted and hunted in irrigated crop fields until 9:00 p.m. on the 10th. Then she headed north and northwest for a 46-mile flight ending up at the George Mead State Wildlife Area, northwest of Stevens Point where she stayed for one day before again moving northwest on a 72 mile flight ending up at a open bog in Sawyer County. Could she be taking a northwest direction to avoid flying over Lake Superior?

Fond du Lac, the snowy owl. Photo by Richard Armstrong

Introduction to “Fond du Lac”

Catching another owl was a partnership effort with Fond du Lac County Audubon Society who took the lead by paying for a new transmitter. Unfortunately no one from the organization was able to join us for the trapping effort. It was amazing to be able to catch three snowy owls. Thanks to Angel Clark, Suzanne Bahls and Scott for their articles on the experience.

The Clark and Bahls family searched for owls on Saturday afternoon and located seven snowy owls!

From a participant:

“On Saturday evening, February 22, 2020, my husband, Pat, informed me we should take our son Ben, to Norton’s Supper Club, on Green Lake, for his 25th birthday. Pat, then mentioned we need to leave a little early to search for snowy owls on the Mackford Prairie. He called his mission, "Operation Snow Storm.” I have never seen a snowy owl in the wild, so I wasn't quite sure what to look for. I thought this was another one of his wild goose chases searching for rare birds with his Madison Audubon buddies. It also makes me nervous when he's driving and looking through binoculars, so I sat in the backseat thinking I would be safer there.

To our surprise we found one!... A female snowy owl was peached on a snowbank. However, she didn't stay on the snowbank for very long. She started to fly south-east and we followed her. It was hard to see her with the naked eye as she flew further and further away… She finally landed again in a snow covered field near a fence line. I also would like to mention, that this is truly like trying to find a needle in a haystack with all the snow and the owl basically being all white. But we did it! And boy, were we proud of ourselves! My husband, Pat, was so excited he called Mark Martin to give him his news report... "Hi, Mark. This is Pat. We spotted a snowy owl south-east on Lake Emily Road," I could hear Mark's voice on the other end. Mark said, "That's great Pat, now find another!" I chuckled to myself. It reminded me of a school child getting a good mark on a paper, and the teacher saying, now do it again on your next paper!

The second spotting was on a telephone pole on the corner of Hickory Road, and Highway A. It was another female snowy owl. We were all in complete awe of this magnificent creature. It seemed as if this particular bird enjoyed the attention and wanted us to take her picture. We took many pictures with our mere camera phones. Then she must have spotted something edible on the ground across Highway A. It took off, swooped down just when there was an oncoming car! I thought my husband was going to jump out of his seat! He screamed, "Oh no, don't get hit by that car!" It did not. The owl made it safely to the other side, and came back to where it was originally peached. However, that seemed like it was very dangerous for the bird. Now I can see that these magnificent creatures need safer places to be. Better places for them to perch and find food.

...From this experience, I have a whole new appreciation for these volunteers and scientists. Now, future generations will be able to experience what we did! Thank you, Project SnowStorm for all your hard work and dedication!”

-Sincerely, Angel Clark

Nine people met on Sunday (February 23) afternoon in Green Lake County east of Lake Maria to catch as many snowy owls as possible. Volunteers included Richard Armstrong, J D Arnston, Mark and Pat Clark from Madison Audubon, Jeff and Suzanne Bahls, and Rick Vant Hoff from the Horicon Marsh Bird Club, and Gene Jacobs and Brad Zinda from Linwood Springs.

From a participant:

“My snowy owl obsession started about thirteen years ago when I went on a “first date” with Jeff Bahls. He took me to see one on highway 49 at Horicon National Wildlife Refuge. Every winter since, I have looked forward to their visits in our neck of the woods. When Jeff and I got married a few years back, we had a small, simple ceremony with our kids and celebrated afterwards with a snowy owl cake! Therefore, a few weeks ago, when Mark Martin contacted Jeff about locating a Snowy Owl to be tagged for tracking, thoughts of actually getting to see one up close was like a dream!

Jeff and I headed over to where we had seen one earlier... off a lightly traveled county road. When we got there, it had relocated to the other side of the road and further away. Gene thought it was still close enough, so he set the trap near the road and we watched… and waited. This owl did not budge. We watched him cough up a pellet and we thought, well, he must be hungry now... Mark Martin, who had been watching with us decided to take a little drive around and see if there were any other Snowies in the area. He found one sitting on a pole on the next road over. We could actually see it from where we were sitting. The problem was the road the second owl was on is a busy road. Mark talked to the landowner and got permission to set a trap on the ground away from the road. It was decided to take a chance on the second owl.

We picked up our trap and drove over to the second location. Brad took the trap and set it within sight of the second owl. We watched and waited again. About ten minutes later, the owl hopped off the pole and flew to the trap. She landed on top of it and then hopped off. She did not get tangled in the fishing line that was used to trap her. She sat a few feet from the trap and looked at it for a few minutes, then walked back to it and jumped on it a couple times, but still did not get tangled in the line. She then flew off about a hundred yards. Our hearts sank. Brad walked to the trap and re-adjusted the fishing line, and came back to the truck. We watched and waited again... Several minutes later she took off flying toward the trap and finally got snagged in the line. Jeff and Brad jumped out of the truck and ran to the trap and went right to work untangling the owl. We got her!

We assisted Gene Jacobs and Brad Zinda in any way we could. During those few hours we caught three adult female Snowy Owls. Two were measured, banded and released back where they were caught. The third snowy was processed and Gene attached a GPS transmitter so Project SNOWstorm biologists can track her movements. It was amazing to witness first-hand the wings, beaks and talons of these gorgeous birds, and to see and work with the people from Madison Audubon and Linwood Springs Research Station. Reflecting on the events of that night still seems like a dream. It was an experience I will dream about for many years to come.”

-Suzanne Bahls

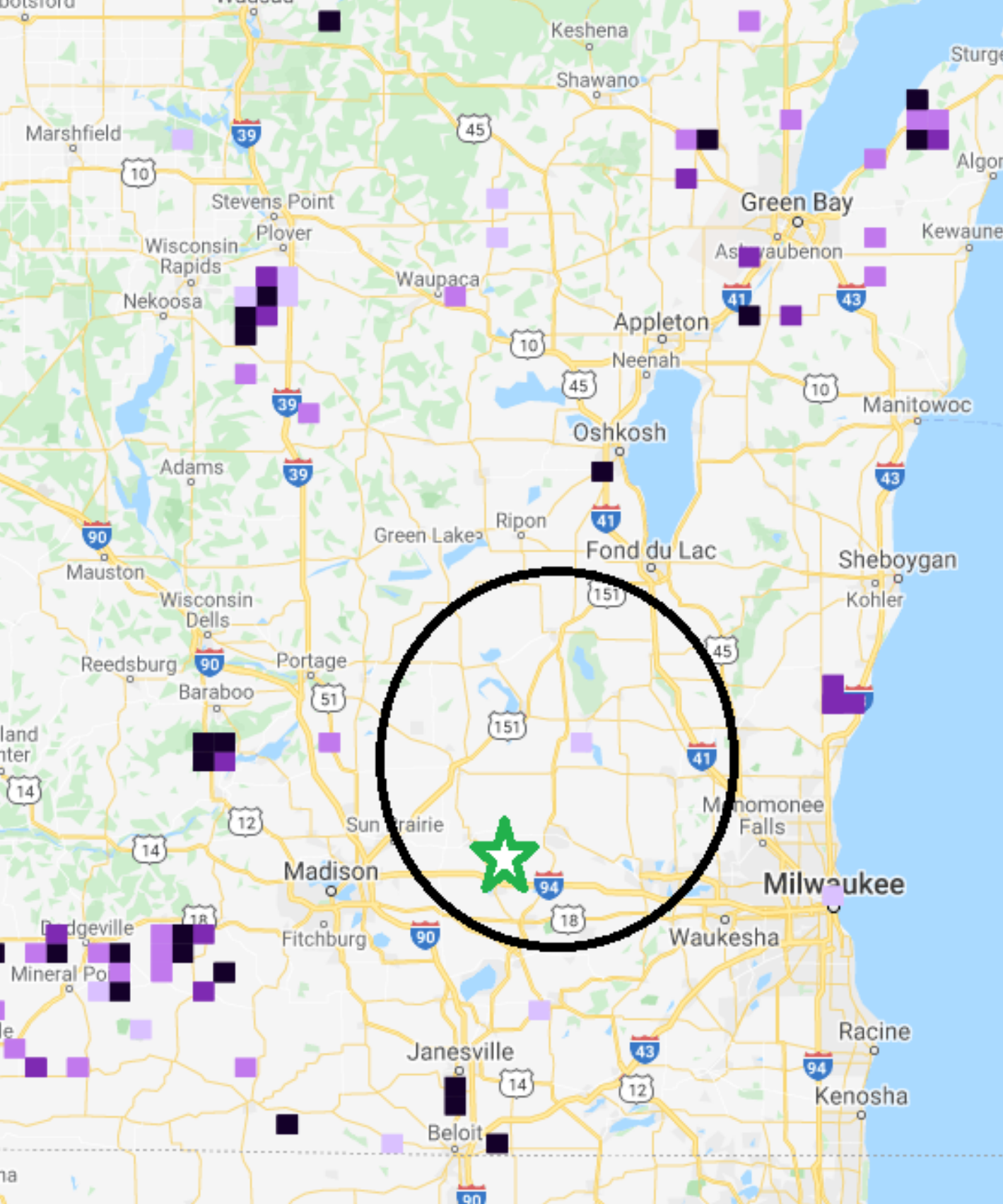

Fond du Lac stayed close to where she was released until March 7 when she moved a few miles north, just south of Green Lake. Her last cell phone was from that area on March 10th. We look forward to seeing her migration northward.

Find more information on the capture and release of three snowy owls at the Project SnowStorm on Scott’s blog post titled Fond du lac, and the Owl-fecta.

We hope that the owls enjoyed their visits to southern Wisconsin. We also wish them safe travels to the land of the midnight sun and hope they return to southern Wisconsin next winter for another vacation.

Thanks to everyone who donated funds for the transmitters, to Gene and Brad from Linwood Springs for trapping and processing the owls, and to the volunteers who reported sightings, assisted with locating owls, taking photographs, trapping, and processing the birds. We hope you follow their journey north.

Written by Mark Martin and Sue Foote-Martin, Goose Pond Sanctuary resident managers, and Graham Steinhauer, land steward