A catchy title but seeing sea ducks at Goose Pond is a very, very rare occurrence. Three species of sea ducks recorded at the pond are the long-tailed duck, black scoter, and white-winged scoter. This feature is on the scoters. In the 41 years since we have lived at Goose Pond, there have been just two days when scoters were present.

The first scoter sighting was a black scoter that Mark found one fall afternoon in the 1980s. The scoter was about 40 feet from Goose Pond Road when Mark drove by and quickly stopped after seeing this unusual duck. It appeared to be a male and was easy to identify with the black body and knob above the bill.

Black scoter photo by Aaron Maizlish FCC

Sam Robbins wrote in 1991 Wisconsin Birdlife that black scoters are an uncommon fall migrant east (Lake Michigan); rare fall and spring migrant elsewhere.”

Sam also reported that “Until 1981, Wisconsin had no record between early June and late September. So it came as a complete surprise to Jim Hale to find a female escorting five downy chicks along the Lake Michigan shore in Door County on 6 July, 1981." Mark worked in the DNR’s Bureau of Research at that time where Jim was the Bureau Director.

According to the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, “Late autumn migration occurs across a broad front, so migrants may turn up almost anywhere in the continent’s interior, usually on lakes and larger rivers, where they normally do not linger long.

Black Scoters nest in the remote north, making their population trends hard to estimate, but they appear to be in decline. A 1993 study of eastern North America estimated a decline in all 3 scoter species at 1% per year between 1955 and 1992, indicating a cumulative decline of 31% over that period. Partners in Flight estimated the 2017 global breeding population at about 500,000 and rated the species a 12 out of 20 on its Continental Concern Score, indicating a species of low concern. Black Scoters form large winter flocks along both Atlantic and Pacific coastlines, though they are scarcer south of the Carolinas and northern California. During late autumn, tens of thousands may migrate southward past prominent headlands or peninsulas. Inland, Black Scoters turn up briefly on lakes or reservoirs, especially when bad weather drives them out of the sky. As with most waterfowl, a spotting scope is useful to get good views.”

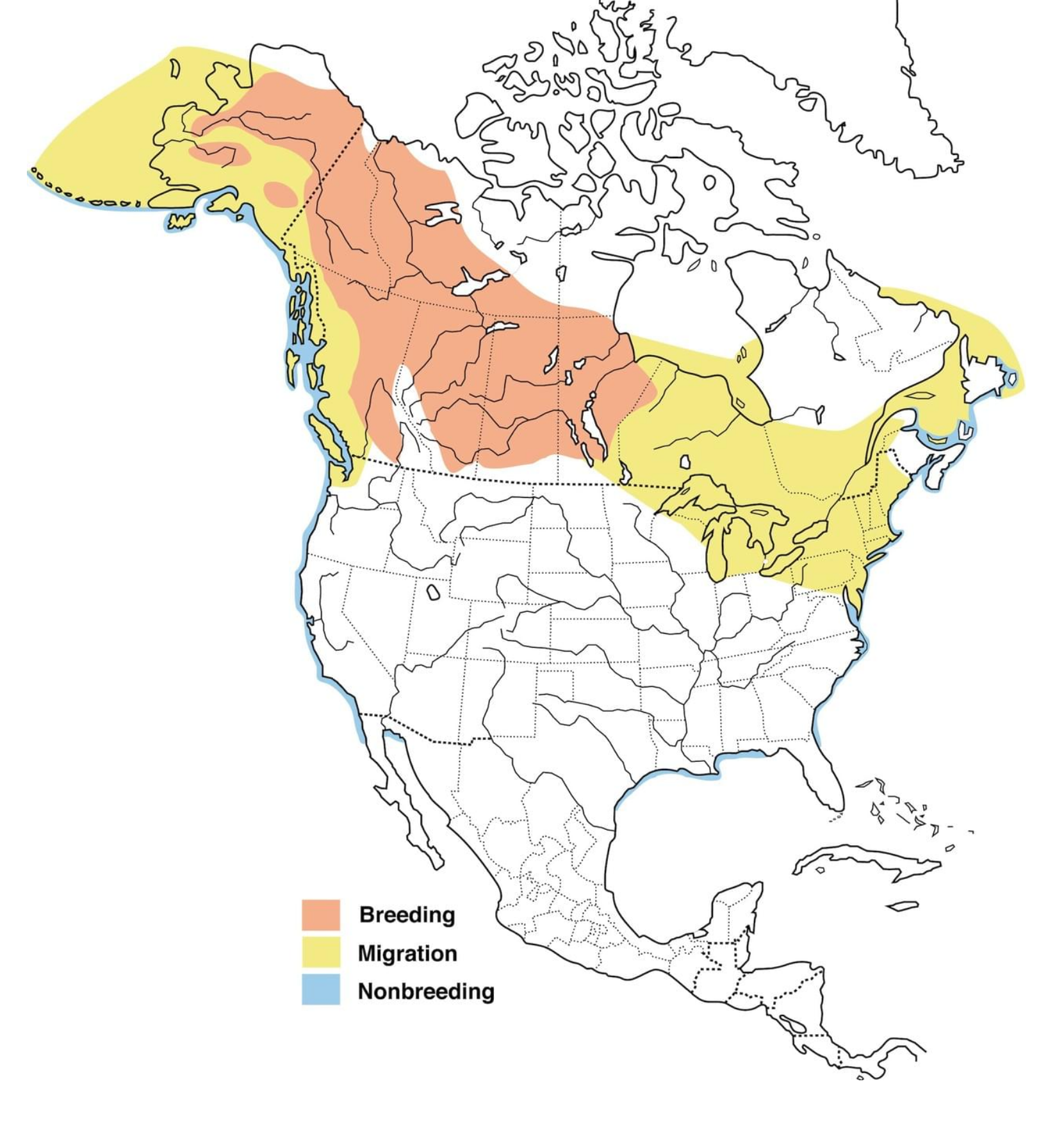

Black scoter range map, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

There must have been bad weather before the fourth weekend in October to the north and east of us. On October 23 to October 25 there were numerous reports of scoters in Dane County. Rare eBird reports had black, white-winged, and surf scoters at Ferchland Place Overlook and Olbrich Park. Black scoters were found at Hudson Park and white-winged scoters were found at Tonyawatha Park, Marshall Park, Schluter Beach, University Bay, Hudson Park, Lake Farm County Park, and Lake Kegonsa State Park in Dane County.

JD Arnston reported on the following observations on October 24 and 25:

“This past weekend, I received several eBird alerts about all three species of scoter being sighted on the Madison lakes. Excited to add them to my life list, I checked out a number areas on the 24th and was lucky enough to see two of the three species—3 black scoters and 1 surf scoter.

The next day, while talking with Mark Martin about my scoter sightings, he suggested keeping an eye out on Goose Pond for scoters as well. That afternoon, I went out to Goose Pond for some birding—hopeful, but not convinced—that I would see any scoters. I surveyed the entire pond but had no luck in the way of a single scoter. After this, I drove around the area, visiting several other wetlands and ponds in search of migratory waterfowl. After seeing many birds but no scoters, I made my way back to Goose Pond, figuring I would give it one more quick look before calling it a day.

As I scanned the pond, I almost couldn't believe it—a group of 8 white-winged scoters near the center of the west pond. Not only was this a lifer for me, but it was also the first record of a white-winged scoter at Goose Pond.” JD’s eBird report contained the following observation. "Juvenile/female plumage. Large bill, especially at the base. Dark colored with the exception of the white eye markings on both sides of the eye. The white wing patch was also visible." Mark, Graham, and Calla searched the next day but it appeared that the scoters had moved on.

Female white-winged scoter photo by Mick Thompson FCC

Male white-winged scoter photo by Mick Thompson FCC

Sam Robbins wrote in 1991 Wisconsin Birdlife that white-winged scoters are an uncommon fall migrant east (Lake Michigan); rare fall and spring migrant elsewhere.”

According to the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, “White-winged Scoters are usually the scarcest of the three scoter species in North America During migration, after heavy storms, or when the Great Lakes have frozen over, they often show up on inland lakes.

White-winged scoter range map, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Biologists know very little about their population trends. Partners in Flight estimates a combined global breeding population of White-winged, Stejneger’s, and Velvet Scoters of 400,000 and rates White-winged Scoter a 13 out of 20 on the Continental Concern Score, indicating a species of low conservation concern. Much research is needed on all three scoter species.”

Until recently, the Common Scoter of Eurasia and Black Scoter of North America (and northeastern Russia) were thought to be the same species. Bill differences between male Common and Black Scoters have been known for centuries, but it took a 2009 study of differences in courtship calls to clinch the case for recognizing them both as full species.

For many years, the Velvet Scoter of western Eurasia and Stejneger’s (Siberian) Scoter of eastern Eurasia were combined with White-winged Scoter as a single species, but in 2019 taxonomists decided to treat them as 3 separate species.

Although the White-winged Scoter winters primarily along the coasts, small numbers winter on the eastern Great Lakes. Populations on the Great Lakes may have declined during the 1970s but now appear to be increasing in response to the invasion of the zebra mussel, a new and abundant food source.

We hope the scoters in the Madison area linger for awhile and that you can get out to see these sea ducks. The white-winged scoter is the 36th species of waterfowl (ducks 27 species), geese (6), and swans (3) on our Goose Pond Bird Species List. We are looking forward to the day when we can add the surf scoter.

Written by Mark Martin and Susan Foote-Martin, Goose Pond Sanctuary resident managers