A young kestrel chick stretches its wings. Photo by Phil Brown

Helping the American kestrel increase its numbers and providing data to the American kestrel Partnership has all the qualities of a good citizen science project for Madison Audubon. Madison Audubon’s volunteers began directly helping kestrels in 1985 when Mark, Sue, and volunteer Greg Geller began erecting kestrel nest boxes at Goose Pond around 1985. The kestrel nest box project really started to take off in 2009 with a coordinator (me) assigned to the project, and then again in 2012 when Mark and Sue ask me to check the nest boxes using a spy camera, a major advancement in the efficiency and effectiveness of monitoring.

A kestrel nest box sits in the prairie, filled with young chicks. Madison Audubon photo

Kestrels need help since the kestrel population in our region declined 41% between 1966 and 2014, partly due to loss of their natural nest sites in tree cavities. Our goal is to reverse that trend by providing nest boxes (which they readily take to), ensuring the boxes are clean, protected from predators, monitoring, and documenting their nesting progress from egg laying to fledging. One example, in 2019 reported by Dave Lucey that demonstrates there are not enough cavities is where a kestrel nested in a wood duck box in the Cross Plains area.

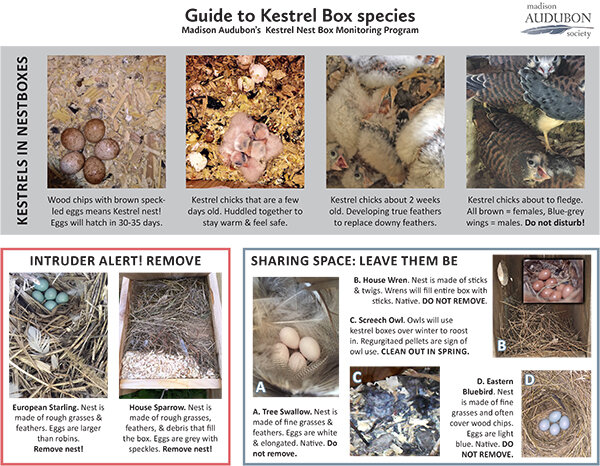

The “kestrel” nests boxes have been used by 10 other species. Our monitors have recorded house sparrow and European starlings that are the two bad competitors for a nest box due to not being a native species. Eastern bluebirds, tree swallows and house wrens are welcomed to use these cavities. A big surprise is when we find a wood duck, hooded merganser, eastern screech owl, great crested flycatcher, or fox squirrel using the boxes. The document below shows what a kestrel nest looks like along with some other users. This is useful information for monitors.

We also work with the Western Great Lakes Bird and Bat Observatory which helps coordinate kestrel nest box projects in Wisconsin. Information gathered while monitoring is sent to the American Kestrel Partnership (AKP). The AKP is under the umbrella organization The Peregrine Fund who help raptors worldwide. Information collected is the nest box physical location, box dimensions, opening orientation, date of field checks, number of eggs or chicks, chick age and is another species using the nest box.

The AKP does not know the exact reason for the decline of kestrel numbers. All this information is useful in hopes of coming up with reasons for their decline. Is it predators, pesticides, change in land use, climate change, loss of natural cavities? Or are there other reasons?

This citizen science project fits well into creating an activity for many people to get involved. Our volunteer base has grown from 1 monitor checking up to 70 nest boxes in 2012 to 45 monitors checking 178 nest boxes over eight counties in 2020. We are monitoring 4.3 % of the 4,106 nest boxes being monitored mostly in Canada and the United States. Our kestrel box project is in the top three in number of boxes being reported to the American Kestrel Partnership.

Volunteer Terri Bleck featured here. Photo provided by Terri

The below quote is from Terri Bleck, one of our newest volunteers. Her sentiments are similar to many other volunteers’ who work on this and other Madison Audubon citizen science projects.

“Last fall I was looking for an organization that I believe in to include in my planned giving and National Audubon and Madison Audubon made perfect sense. I am concerned about our planet and environment and the ever-increasing extinction of wildlife. National Audubon and all their local chapters do crucial work toward saving the places important for birds and other wildlife to exist. Becoming a member of Madison Audubon provided opportunities for me to become involved in their mission by becoming a citizen scientist.

This spring I signed up to be involved in the Bald Eagle Nest Watch and the American Kestrel Nest Box Monitoring programs. Each week, I thoroughly enjoyed my experience observing and photographing these magnificent creatures. I felt like I belonged to a secret club that allowed me a free pass to learn where these birds nested. I witnessed the whole nesting process of an American Kestrel, from mauve speckled eggs that hatched into white fluff balls, then developed dark feathers on their backs and wings, and finally morphed into a beautiful Kestrel. What a grand experience!” Terri’s photos are below.

Another part of the kestrel project has been the ability to place a Fish and Wildlife Service metal identification band on the legs of young and adults, especially females, taking our citizen science up a level. The band is useful in learning where kestrels move. When a kestrel is recaptured or found dead the band number can be reported and this information is sent back to the original bander. The last five years Madison Audubon been fortunate to have Janet and Amber Eschenbauch from the Central Wisconsin Kestrel Research program come down from the Stevens Point area to band kestrels in the Goose Pond area and south-central Columbia County.

Amber (left) and Janet (right) Eschenbauch are Wisconsin’s experts on kestrels. Janet possesses a master bander permit, allowing her to conduct the banding activities for Madison Audubon. Madison Audubon photo

The Eschenbauchs have been banding kestrels at Buena Vista Marsh for years and when contacted were more than happy to come to Goose Pond. Recaptures include an eight-year-old female that was banded 90 miles south near Rockford, Illinois. Janet recaptured a male banded as a chick near Rio that was found nesting at her project at the Buena Vista Marsh the following year. In June 2019, a male kestrel chick was banded and fledged the first week of July. Unfortunately, he was found dead at the Dane County Airport three weeks later. So far, we have recaptured 24 adults. All adults were banded in the Goose Pond area or south-central Columbia County. Adults were recaptured in the same box or they were found a couple miles down the road. Some pairs stayed together the following year while others split up.

Along with the banding, feather and toenail samples are taken and submitted to Boise State University for study. The plucked feather is used to identify wintering grounds, determine population change and assess the impacts of climate change. Toenail samples will show something like found on “ancestery.com”. Wisconsin birds are shown to be part of the eastern United States population.

In 2019 Amber Eschenbauch bands a kestrel chick as Madison Audubon members watch, completely fascinated! Madison Audubon photo

An exciting part of banding is educating the public. For four years the public has attended the banding sessions. Janet and Amber are great educational ambassadors. They talk about the reasons for their work and everything about kestrels. The attendees can ask many questions and the Eschenbauchs have yet to be stumped. Youngsters and adults alike love to hold the chicks while the birds are waiting their turn for a band. This has been such a positive experience that several of the present-day monitors came from these banding experiences. They saw the work that MAS is doing and wanted to get involved. To help support this project MAS does ask for a small donation from attendees.

An example of how the data we have been collecting is useful to more than the AKP are the studies done by two universities. One is the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee and Tufts University in Boston—https://arcg.is/1G5iTT0. They both used our data in hopes to identify the best locations to place nest boxes. We are trying to use their information as we erect additional boxes. Jim Hess is having great success with boxes erected in Lafayette County near trout streams.

Data that has been collected locally has given us a better idea of when kestrels start nesting. In 2012 we were thinking that we should have the nest box ready at the end of April. After charting out this past two-year nesting phenology data it shows that we need to be ready much earlier.

This high-level view of the kestrel phenology chart helps us track how early in the season we should be prepared for kestrels nesting in southern Wisconsin. For more information about the phenology chart, contact Brand at brandsmith@charter.net

There are several organizations that have been involved with our kestrel project. Two of which are Dane County Humane Society’s Wildlife Center and the Raptor Education Group Inc (REGI) in Antigo. Two years ago, the Wildlife Center contacted Madison Audubon wanting to know if we could place four orphan kestrel chicks that came from a construction site. It just so happened we were banding chicks the very next day. With Janet Eschenbauch supervising, there were two main concerns. 1) Making sure the new chicks were the same age as the chicks in the nest box and 2) could the parents provide enough food. Janet felt comfortable placing the new chicks because we knew how old all the chicks were and they all looked extremely healthy, meaning that they have been getting plenty of food. We then placed one chick in each of four boxes—read the fully story here. That same year the Wildlife Center was contacted about another construction site where the birds were still in a home to be razed. They asked if we had a nest box to be placed near the existing nest site. This story also ended well. We erected a nest box, moved the young, and the adults continued feeding their young.

The REGI group is a rehabilitator organization and has been a resource when we run into injury questions. Two years ago, while banding, we found an adult with an injured foot. It was bad enough that we were not sure the young could receive enough food. We were considering moving the existing young to other boxes, but we felt that would be too risky. Working with the Eschenbauchs and the REGI group, it was determined that if we could supplement a food source the young could survive, and the adult would need to do the best she could to survive. We found a food source at the DNR Poynette Game Farm where they raise pheasants. Graham Steinhauer, Goose Pond Sanctuary land steward, and Tanner Pettit, Goose Pond Sanctuary summer intern, had the duty of placing food into the box every other day. Tanner reported that the hen got quite use to his opening the box and placing the food items inside. The chicks fledged, and the adult also left the box. She was banded so we hope with any luck we can recapture her to see how she is doing.

This year we found one chick with the back toe missing on one leg. With this injury the bird would not be able to perch and it also appeared to be the runt of the family. REGI recommended that the chick should be removed and brought up for rehabilitation. Janet made the delivery and at last report, the chick was doing better.

Madison Audubon also partners with many organizations for nest box placement including private landowners, State Wildlife Areas, Fish and Wildlife Waterfowl Production Areas, and Dane and Jefferson County Parks. Thank you to all of these partners!

Over the years there have been eagle scout badges earned associated with the kestrel project. Cal Jansen had a successful Eagle Project in 2019. With Madison Audubon guidance, Cal lead a team of four other scouts in building ten nest box structures and installing four nest boxes on Ho-Chunk Nation property at the former Badger Ordinance property near Baraboo. They also monitored five boxes over the breeding season. Four of the five boxes were active and two of the parents have become monitors and will be volunteering in the future. Cal did a great job coordinating the scouts and earned his Eagle Scout.

2020 was a different year for monitoring due to the COVID-19 virus. At first Madison Audubon needed to make sure that we could do our project safely. Due to the monitoring being a solo or family unit activity the monitoring was determined that it could be done safely. I had several people tell me they enjoyed the project even more this year because they had a reason to safely leave the house and get out into nature. The banding was a different story. We did not actively try to capture adults due to the inability to social distance. We also canceled the public interaction while banding but were able to safely band chicks.

In closing I want to mention a first-time highlight of the project. In Lafayette County, Jim Hess monitoring a nest box that had a second clutch fledged in the same box. Eggs were laid in the box two days after the first clutch fledged. This is a rather rare and first-time occurrence for our project. I also would like to highlight the growth of membership with this citizen science project. At a time when volunteering in an organization is dropping nationwide, Madison Audubon has a project that has grown from one monitor to 45 monitors in nine years. I believe this is due to Madison Audubon having a project that gives its volunteers an opportunity to get outside, get their hands dirty, and learn about nature. I cannot tell you how many times I have had volunteers tell me how excited they are with seeing eggs or a chick in their box for the first time. Or when an adult bird may dive bomb them while getting ready to place a camera into the nest box. This enthusiasm is what motivates me to be the coordinator of this project.

Brand Smith coordinates the kestrel citizen science program on a volunteer basis. Thank you Brand! Madison Audubon photo

Thanks to Mark, Sue, Graham, Tanner, and Brenna with Madison Audubon and “Citizen Scientists” that helped construct, erect, and monitor nest boxes and assist with banding young and adults. Brenna is the person that does the publicity and lines up the field trip participants. This is a team effort of around 50 people.

I look forward to a “normal” year in 2021 (fingers crossed!) and look forward to seeing many of you participate in monitoring or banding.

Written by Brand Smith, volunteer, Madison Audubon’s Kestrel Nest Box Monitoring Program coordinator