Lapland Longspurs are an interesting species with an interesting name. They nest worldwide in the high arctic, including the Lapland region of Scandinavia.

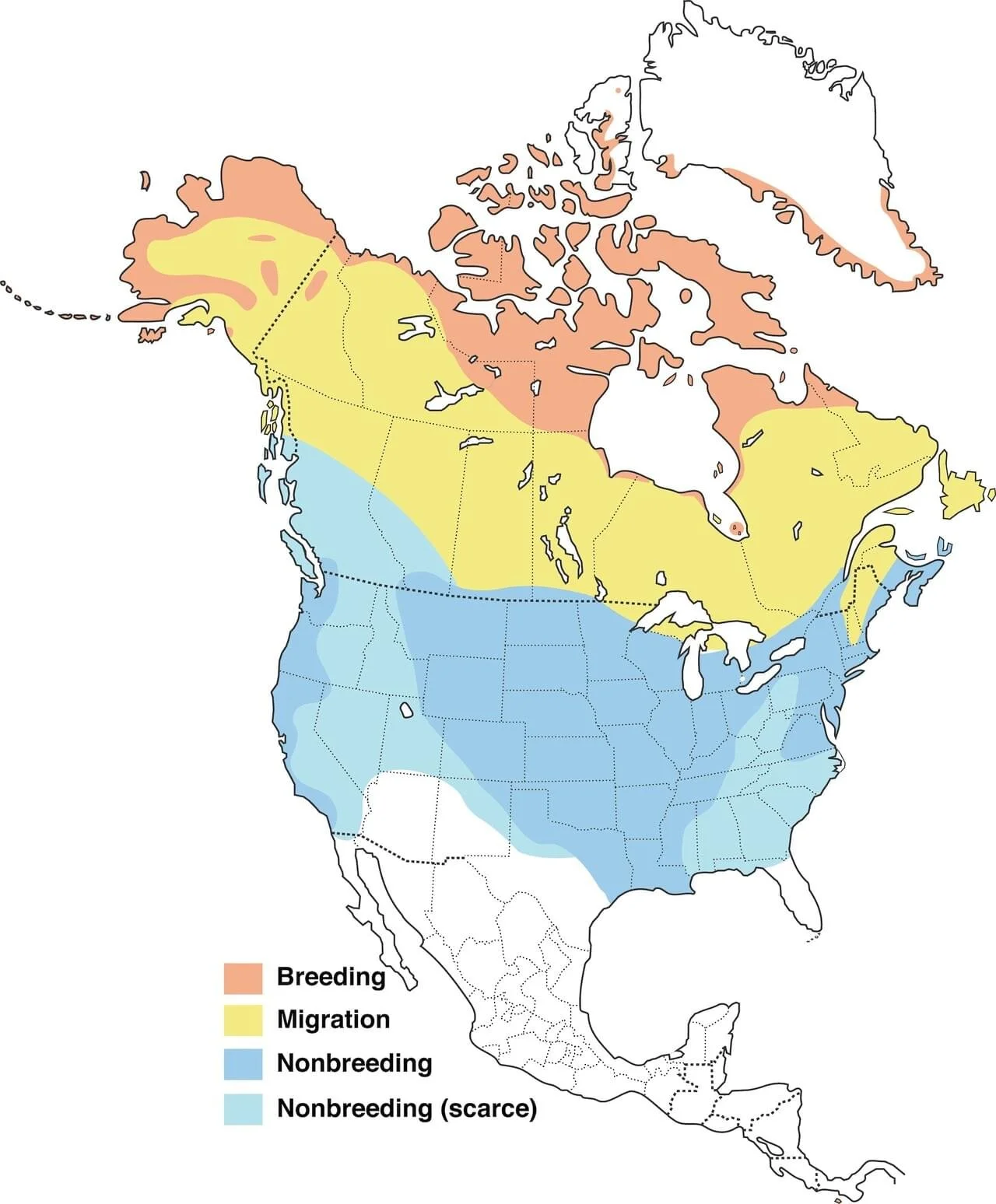

Range map of Lapland Longspurs in North America (courtesy of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology).

These birds will migrate through and winter in southern Wisconsin, first showing up in late October and departing after the first half of April. When flying in loose, undulating flocks, sometimes mixed with Snow Buntings and Horned Larks, Lapland Longspurs are often heard giving high-pitched, short, rattling prrrt calls—this is a key way to identify them. Our high count at Goose Pond Sanctuary was 300 birds on April 13, 2012.

Three eBird reports noted Lapland Longspurs migrating over Goose Pond during the last week of October. Pat Ready volunteered at our Scope Day outing on October 26 and saw small numbers. Later that day, Judith James reported “one small flock of 11 being blown around, but never landed.”

In North America, this species winters in wide open spaces in the United States. One of the best locations to see wintering longspurs is near Arlington in the Empire Prairie area now dominated by agriculture. They like to feed along roadsides on annual weed seeds, such as foxtail grass. In winters with deep snow, they move south of Wisconsin to areas with less snow cover and more food. The Poynette Christmas Bird Count (CBC) has been held in December for 52 years. Longspurs have been reported on 26 counts, including five years with over 300 found. During the 2017 Poynette CBC, a total of 1,973 Lapland Longspurs were found.

Lapland Longspurs forage for seeds under a light dusting of snow (photo by Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren).

The good news about Lapland Longspur populations is that they appear to have remained mostly stable over the last half-century. They are one of the most abundant breeding songbirds in North America. Partners in Flight estimates a global breeding population of 140 million, with an estimated 66 million of those breeding in North America.

On January 14, 2023, Mike Myers and Jon Peacock were conducting a winter raptor count when they came across a large flock of Lapland Longspurs, conservatively estimating at least 2,000–2,500 individuals: “We initially saw a flock of at least 250 feeding and flying on the east side of Hopkins, and then saw a few hundred flying in from the west toward us. As we watched those we saw a more distant and far larger flock of well over 1,500 flying above the crest of the small hill to our west.”

Thousands of Lapland Longspurs take flight over an agricultural field in January 2023 (photo by Mike Myers).

Lapland Longspurs may be easy to overlook, but are well worth looking for in our area during the next few months!

Written by Mark Martin and Susan Foote-Martin, Goose Pond sanctuary managers.

Cover image by Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren. A Lapland Longspur in nonbreeding plumage forages on the ground.

More Cool facts about Lapland Longspurs from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s all about birds:

Lapland Longspur in breeding plumage (photo by Peter Pearsall/USFWS)/

Lapland Longspurs are busy. During summer, they eat an estimated 3,000 to 10,000 seeds and insects per day, plus feed their nestlings an additional 3,000 insects per day.

The name “longspur” refers to the unusually long hind claw on this species and others in its genus.

Of the four species of longspurs that can be found in North America, the Lapland Longspur is the only one that can be found outside of North America. Its range encircles the northern reaches of the Northern Hemisphere and it’s a common breeding bird in Eurasia, where it’s known as Lapland Bunting.

Some winter flocks of Lapland Longspurs have been estimated to contain 4 million birds.