King of the cattail, the wicked black bird with his yellow epaulets flares his wings, exposing scarlet shoulders and a penchant for conflict. We are encountering, of course, the red-winged blackbird, one of the most abundant birds on the continent of North America.

Their territoriality sticks with many people, be it on bike paths, wetland walks, or a hike near some cattails. Male red-winged blackbirds spend more than a quarter of daylight hours defending territory. A number of hypotheses might explain the fierce defense of red-winged blackbirds. First, the parental investment theory holds that as the age of the nest increases so will the territoriality of the parents. Research suggests this is a strong tendency for red-winged blackbirds, and this theory further predicts that territoriality will increase with an increased clutch or brood size, which is indeed the case for these blackbirds.

Photo by Monica Hall

Interestingly, a Journal Sentinel article was published last year on June 29, 2018 detailing red-winged blackbird “attacks” on pedestrians along the lakeshore. These were likely birds with defending nestlings about to fledge; according to the first Breeding Bird Atlas, the median fledgling date was July 1. These blackbird attacks were desperate attempts to protect their investment in young, and the fiercest attackers might have had more young to protect.

Second, the renesting potential hypothesis predicts that nests later in the season will be defended more fiercely due to slim odds of successfully reproducing again so late in the season. Again, this appears to hold true for male red-winged blackbirds.

An unamused sandhill crane getting mobbed by a red-winged blackbird. Photo by Arlene Koziol

A red-winged blackbird mobs a swan family to protect a nearby nest. Photo by Alrene Koziol

A story, from Antigo on August 11, 2017 shows pictures of a red-winged blackbird attacking and even landing on a bald eagle. According to the photographer, there was a nest nearby. Here, again, we see an extreme example of aggressiveness in this bird, and it can be explained by the renesting potential hypothesis, since the odds of the bird renesting and successfully raising a clutch after August 11 were near zero. The latest date for fledged young according to data from the first Breeding Bird Atlas was August 19, so if the chicks in this nest had not yet fledged, they were likely a second or third nesting attempt.

In summary, early on in the season, early to mid-June, the aggressive birds are likely protecting a nest, and that nest probably is farther along and holding more eggs based on the aggressiveness of the bird. Later in the season, red-winged blackbirds will fiercely defend a renesting attempt, as it’s the last chance for the bird to reproduce that season.

While extremely common and abundant, red-winged blackbirds have undergone a 30% population decline since 1966. This might be attributed to a number of factors, including continent-wide wetland losses and degradation. While we’re not at risk of losing red-winged blackbirds any time soon, their overall decline suggests a worsening of habitat, especially for wetland birds.

Red-winged blackbird nest parasitized by a brown-headed cowbird in an upland setting. Photo by Drew Harry

Another reason to protect these wetland habitats is that red-winged blackbirds have reproductive success in wetlands and marshes. According to the Breeding Bird Survey, only 2% of nests in marshes were parasitized by brown-headed cowbirds, whereas 17% were parasitized in upland settings. Nest success was 48% in wetlands but only 33% in uplands.

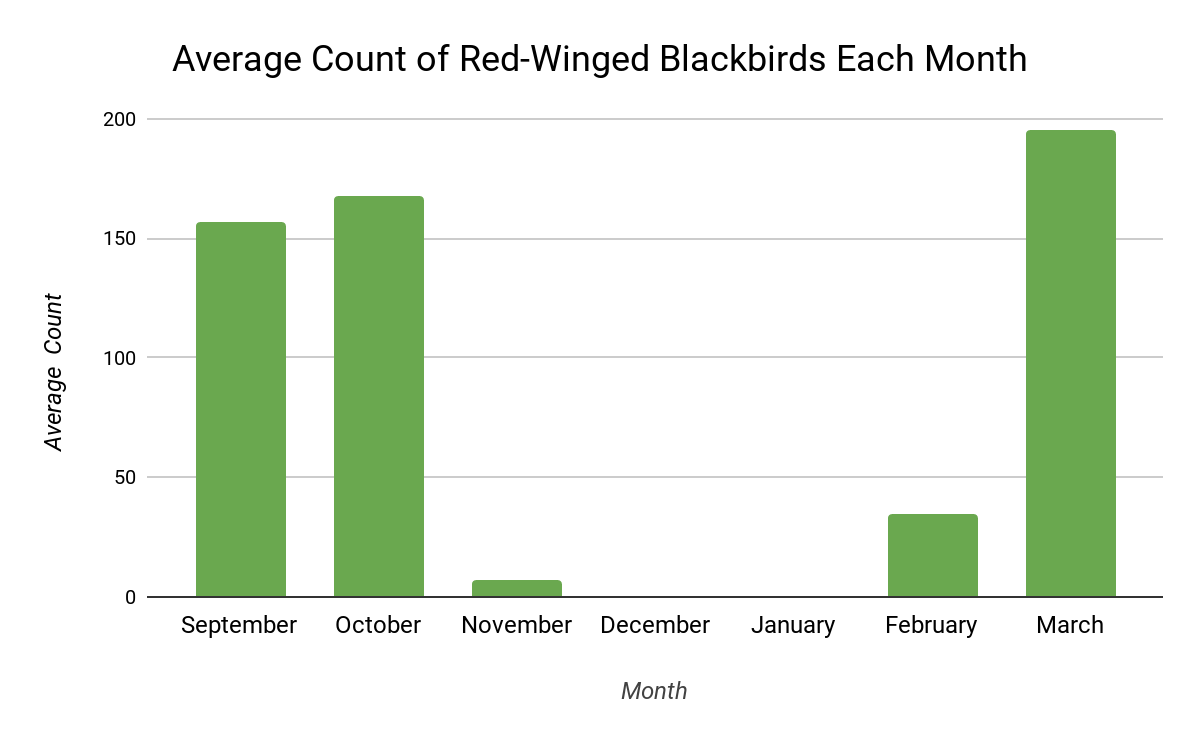

At Faville Grove you can find boisterous red-winged blackbirds throughout the sanctuary. They’ve just returned to the area in the past week.

Written by Drew Harry, Faville Grove Sanctuary land steward

Cover photo: Kelly Colgan Azar