You know them. They’re found everywhere from marshes to roadsides to drier meadows and crop fields. They have that distinct conk-la-ree! song that plays on repeat all spring and summer. And their bright red wing patch (called an epaulet) makes them easy to identify when you’re out in the field. Though red-winged blackbirds are extremely common here in Wisconsin, they are anything but ordinary.

A female red-winged blackbird scores lunch in the form of grasshoppers. Photo by Arlene Koziol

Here at Goose Pond, red-winged blackbirds are the most abundant grassland bird we have. Often, in the summer, they are foraging on the ground for insects like beetles, caterpillars, and grasshoppers. In the fall, they are usually foraging for seeds in huge flocks around our food plots. Sometimes these flocks can have a hundred birds or more in them and they are often comprised of more than just blackbirds. To avoid provoking aggressive responses from each other, males will hide most of their bright wing plumage. Instead of seeing the bright red, you will most likely see just a thin line of yellow. This allows everyone to eat peacefully.

Red-winged blackbird range map. By Cornell Lab of Ornithology

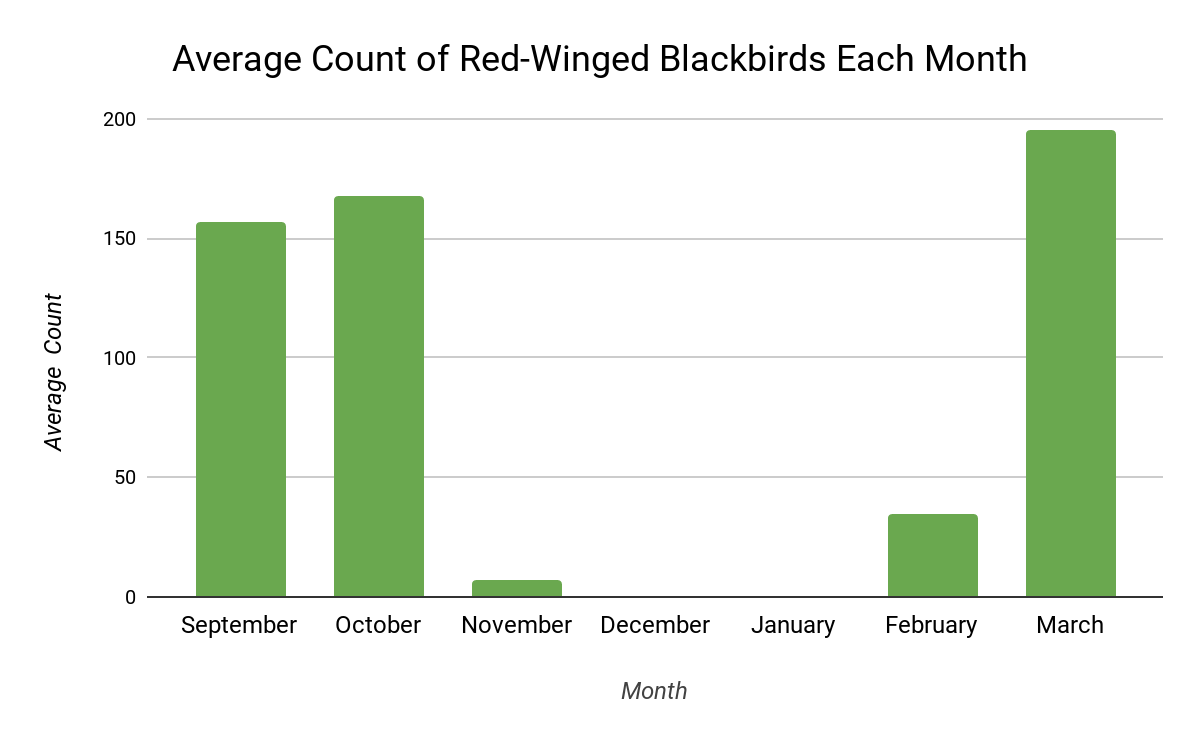

Red-winged blackbirds have a wide range that spans across the country and are year-round residents in most states. In 2017, Maia Persche, with assistance of Jim Otto, conducted counts of red-winged blackbirds seen at the seven-acre food plot from August-April. The data they collected is consistent with what we know about red-winged blackbird migrations. Fall migration for these birds starts in mid-September and goes until early November. At Goose Pond, we saw our red-winged blackbird numbers drop significantly in early November as they headed south. Spring migration starts in early March and goes until mid-May. At Goose Pond, we saw our numbers jump significantly as the red-winged blackbirds came in, ready to establish their territories. As is common in southern Wisconsin, no red-winged blackbirds were seen during the cold winter months.

Goose Pond Sanctuary’ is host to many red-winged blackbirds for much of the year… until winter!

Migration flocks are a sight to see. In Samuel D. Robbins Jr.’s book Wisconsin Birdlife, he quotes a detailed recording of W.E. Synder from Beaver Dam, WI:

“On November 9, 1924, there occurred here, about 4 p.m., a flight of blackbirds, the like of which no local resident ever saw before. The procession, passing from due north to due south, was of such length that those in the lead as well as those in the rear, faded out into mere specks...the flight lasted for a full half hour. The flight was at a great height, a solid column, unbroken by any bunched formation.”

Though red-winged blackbird populations have actually declined by over 30% throughout most of their range between 1966 and 2014, you can still see them fly in huge droves along their migratory routes. In 2014, Partners in Flight estimated their global breeding population was still around 130 million. Be on the look-out for them for the rest of November because pretty soon they’ll be gone for the winter season!

A red-winged blackbird does his best at shooing this sandhill crane from his nearby nest. Photo by Arlene Koziol

Their numbers aren’t the only thing impressive about this species either. As many of you may know, red-winged blackbirds, particularly males, are outright bold and aggressive to anyone who steps, scuttles, or soars into their territory. You can often see males perched above their territories singing, puffing out their wings, and displaying their epaulets. I have many recollections at Goose Pond this summer watching red-winged blackbirds chase out northern harriers and sandhill cranes (who actually prey upon their nests). Mobs will quickly fly out, staying above and behind their predator in order to drive them away. Red-winged blackbirds even managed to gain the attention of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel this summer after several maintenance workers and joggers complained about being pecked in the head while minding their own business!

I’ve had similar experiences myself. While out digging parsnip in our Jill’s south prairie this summer, I was around a red-winged blackbird nest. Both the male and female zoomed around above me demanding that I leave at once. If only I could speak to them and tell them I was trying to help! I cannot blame them for being so territorial; they are just being good parents and protecting their home, after all. There’s no need to be afraid of these guys — you just need to give them the space and respect they deserve.

A male red-winged blackbird sings his heart out. Photo by Kelly Colgan Azar

In 2016, Heather Inzalaco conducted breeding pair surveys and found 365 pairs of red-wings at the Goose Pond prairies. Between Sue Ames, Ankenbrandt, Hopkins, and Wood Family Prairies, she counted a total of 166 breeding pairs of red-winged blackbirds in 219 acres! Wood Family had the highest abundance with 57 breeding pairs over 60 acres; that’s almost one breeding pair per acre! Those are numbers we like to see here and we’re quite thankful to have the habitat and resources to support these blackbirds and their young.

These birds will hold a special place in my memory this year -- I started my internship at Goose Pond when the blackbirds arrived and soon it will end as all the blackbirds leave. I am looking forward to seeing them return next spring.

A flock of red-winged blackbirds move through Goose Pond Prairie. Photo taken by Goose Pond’s DNR Project Snapshot trail camera.

Written by Jacqueline Komada, Goose Pond Sanctuary intern