Since it began continuous operation in early 2021, the Goose Pond Motus Tower has detected a Sora, a Golden-winged Warbler, three Rusty Blackbirds, and four Swainson’s Thrushes. At Goose Pond, Soras are common and Rusty Blackbirds are uncommon. Golden-winged Warblers and Swainson's Thrushes are on the Goose Pond bird list, but neither have been reported to eBird since it was launched in 2002. It makes you wonder what else is flying around up there.

Sam Robbins writes in Wisconsin Birdlife, “Swainson’s thrush is one of the few species that can be identified by a trained ear. I have heard upwards of 500 Swainson’s on a single night.” The Swainson’s Thrush is easily confused by sight with other thrushes, but their eyering is buffy or cream colored as opposed to the distinct white eyering of similar species. They breed in the understory of conifer forests in southern Canada from coast to coast and some northern forests of the United States including around a dozen confirmed instances during the Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas II. All four Swainson’s Thrushes that passed by Goose Pond were tagged in British Columbia, but one particular individual, bird #57677, has been detected by six Motus towers detailing a journey of over 5,300 miles.

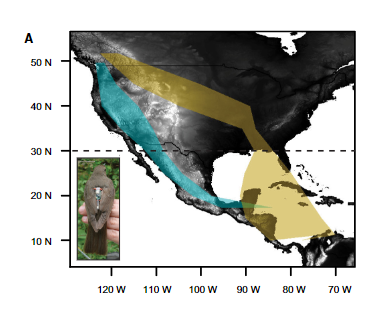

The motus tower map showing the movements of Swainson’s Thrush #57677. Map courtesy of Motus Wildlife Tracking

Out of the ten Motus towers in Wisconsin, four of them have detected a total of 16 individual Swainson’s Thrushes from British Columbia. To date, none of those have been picked up in South America like our intrepid friend #57677.

It’s easy to gloss over bird tracking projects and assume that their goal is to better understand migration. The research project responsible for tagging Swainson’s Thrushes in British Columbia with Motus transmitters, Investigation migratory tendencies of SWTH in a sub-species hybrid zone in the Interior of British Columbia (the predecessor of this is The Genetics of Seasonal Migration and Plumage Color), is trying to answer a much bigger set of questions. How does one species split into two (speciation)? What role does genetics play in that process? How is migration involved?

Russet-backed Swainson’s Thrush. Photo by Andrew Reding FCC

Olive-backed Swainson’s Thrush. Photo by Matt Reinbold FCC

There are two major groups of Swainson’s Thrushes, coastal and inland. Coastal birds (russet-backed) have redder feathers and tend to begin their migration directly south toward Mexico and Central America while inland birds (olive-backed) have olive colored feathers and migrate southeast through the continental United States toward South America. Although the two groups are separated spatially and demonstrate differences in migration pattern and plumage, there is a small region in the Cascade Range of British Columbia where both groups nest and sometimes interbreed. This is known as a hybrid zone, and it allows researchers to study drivers of speciation. The Genetics of Seasonal Migration and Plumage Color is a novel study in that it’s “the first time data from birds tracked over the entire year have been combined with genomic data to show that migratory routes are genetically determined.”

Researchers found that pure coastal thrushes migrate through suitable habitat on the west side of the Rocky Mountains and pure inland coastal thrushes migrate through suitable habitat on the eastern side, but hybrids tend to cut straight through. Arid and mountainous habitats are unsuitable and difficult to navigate for Swainson’s Thrushes, likely causing higher mortality rates for hybrids and reinforcing long term genetic division between the two groups.

Other studies have shown significant genetic differences between resident and migratory monarch butterflies, resident and migratory salmonids (members of the salmon family), and willow warbler populations with different migratory orientations. This suggests that groups within a species do not have to be isolated throughout their entire life history (e.g. breeding and wintering) to diverge into separate species over time, and that similar mechanisms may be driving speciation in very distantly related migratory animal groups.

When we erected the Goose Pond Motus tower, we didn’t know what to expect. Migrating Mallards or Red-tailed hawks seemed likely at the time. It’s rewarding to assist researchers in gathering data for such complex and important work, even though our connection to Swainson’s Thrushes was in no way planned. 329 total Swainson’s Thrushes were tagged with Motus transmitters (95 active during fall migration 2021) in association with Investigation migratory tendencies of SWTH in a sub-species hybrid zone in the Interior of British Columbia. We hope that some of them pass by Goose Pond again this spring on their return journey to the Cascades.

Thanks to Don Schmidt and Chip Plummer for their work in constructing and installing the Motus Tower, JD Arnston for managing the data, Western Great Lakes Bird and Bat Observatory and Birds Canada for their guidance, and members and donors like you who funded the project.

Written by Graham Steinhauer, Goose Pond Sanctuary land steward

Cover photo by Kelly Colgan Azar