Emma Pelton poses in front of some milkweed (photo by Emma Pelton)

In this episode, we answer questions like "How do monarchs know where to go on their migration?" and learn about the Monarch Butterfly mysteries still to be uncovered with our Monarch Butterfly expert Emma Pelton, conservation biologist for the Xerces Society.

See the work of the Xerces Society

Subscribe to QuACK on Spotify, iHeart Radio, Apple Podcasts, or your favorite podcast app!

Transcription

Hey, and welcome to Questions Asked by Curious Kids or QuACK, a podcast made by Southern Wisconsin Bird Alliance. This is a podcast where we gather questions about nature from kids to be answered with a local expert. My name is Mickenzee, I'm an educator, and I'll be the host for this series. And this episode I'll be interviewing Emma Pelton, a conservation biologist at the Xerces Society. I know I usually have experts that are in Wisconsin, but this time our expert is someone who grew up in Madison, and her super cool job has her living in Portland, Oregon. And today she'll be talking about monarch butterflies. Let's get started with Emma.

-----

Mickenzee: Hey, Emma, welcome to the show. So I know you grew up in Wisconsin, and maybe we'll talk about that in a little bit. But before we get started with the questions from the kids, can you tell us a little bit about your job?

Emma: Yeah. Thanks so much for having me. I love my job. I work at the Xerces Society, and we're a nonprofit focused on invertebrates and their habitats. So we broadly work, across anything that doesn't have a spine that lives on land or freshwater. And so we work on many different insects, but also mussels and snails and things of that kind. And I get to work specifically at my job on Western Monarch Butterflies. So monarchs that grow up as caterpillars west of the Rocky Mountains and primarily overwinter or, another fancy word for just spending the winter at coastal groves of trees in mostly, coastal California and then all the way down into Baja California, which is northern Mexico.

Mickenzee: Wow. So listeners might not know this, but Emma is calling in from Portland, Oregon. Yeah. So you're out on the coast and that. So that's a different population of butterflies than the ones we see here in Madison, right?

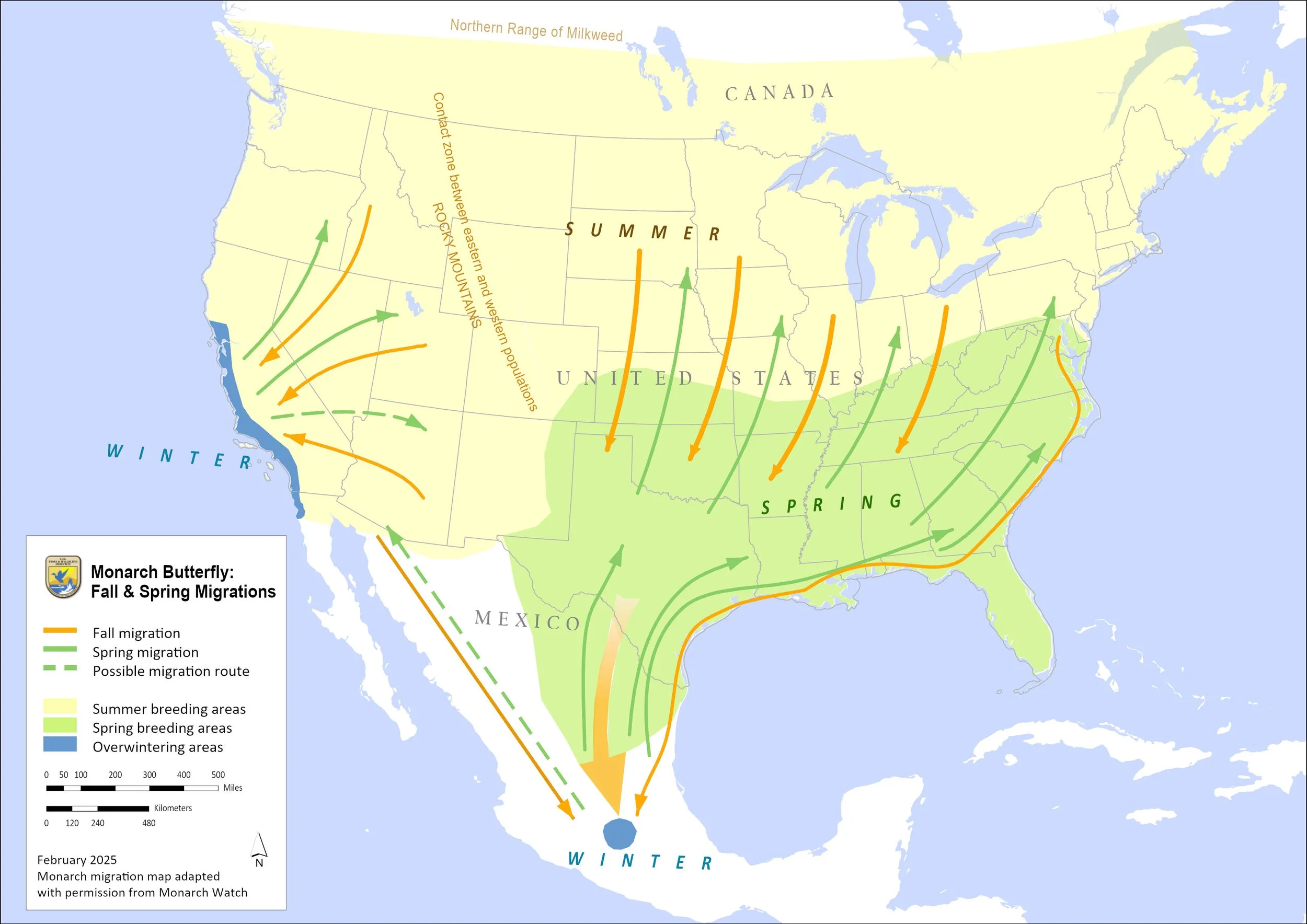

Map of Monarch Migration (photo by USFWS)

Emma: Yeah, there's the eastern population and the western population. But we know they're not genetically distinct. And they cross those mountains. Now there's unique migration. So the monarchs you all see in Wisconsin go down and funnel through Texas and Oklahoma, and then they go into, Michoacan area of Mexico and are spending the winter in really high mountains in the middle of the continent, as opposed to the butterflies I work on, which are spread out across the west. And then they go to coastal California, really close to the beach. So both populations have this very different migratory path, but they're really the same butterflies. And we know there's a lot of flow between the two populations.

Mickenzee: Very cool. I think if I were a butterfly, I'd probably be a Western Monarch so that I could spend my winter on the beach too, that sounds pretty cool.

Emma: I know, they choose a really good, convenient location, like trekking into high forests in Mexico.

Mickenzee: And Emma, you grew up here around Madison. And did you have an interest in monarchs even when you lived in Wisconsin?

Emma: Yeah, I definitely grew up loving the outdoors, loving being outside. And my dream was definitely if I could work, not in an office, but be outside. And now I work in an office and I get to be outside. But, yeah, my parents took us, you know, camping and hiking and canoeing and just even, like, exploring in Six Mile Creek. I grew up north of Madison in Waunakee, just all those, you know, experiences to have really, hands-on engagement with the world. And so definitely always had an interest. And I remember, finding a monarch caterpillar with my sister in our garden and raising it and letting it, you know, out in the world and then liking to imagine that every year that same butterfly was coming to visit us. Yeah, that butterfly was long gone. But maybe, it's great great grandchildren who were coming back. So, yeah, I think that that connection and what I love about monarchs is that they're found in so many places. They are not just found, you know, in natural areas or pristine habitat. They're found in milkweed growing in a crack in your driveway. You know, that can host a monarch. So I think just the ability for these butterflies to move over huge landscapes and, you know, visit people in rural areas and natural areas in cities and suburbs and everywhere in between is really incredible.

Mickenzee: Yeah, it's a really cool species that a lot of people can be familiar with. So all of our questions today were submitted by the third graders at Lincoln Elementary School. Our first question is “Why do monarchs migrate?”

Emma: It's a great question, and I think the most honest answer is we are still learning why they migrate. But we have some ideas. And so, like birds, you know, they're often tracking the weather, they're tracking food. They may be escaping diseases or predators, things that want to eat them. So if you think about Wisconsin in the winter, it's not the best place if you're a little fragile butterfly. So you're going to need to escape those freezing temperatures. And so we know that in the fall that they're really driven to escape those freezing temperatures to go somewhere where they can, it's warm enough that they're not going to freeze, but it's not so warm that they're going to use up all of their energy.

Mickenzee: So what is, and this is my own question, So what is the signal to butterflies to start migrating?

Monarch emerging on drying plant (photo by USFWS)

Emma: This, I think, is even more of a mystery. We’re still figuring this out because, you know, I mean, bird migrations. Incredible. But you think about birds, you know, live on average multiple years, they’re maybe with other birds, you know, a parent or a flock can teach them. These butterflies are really on their own. You know, they didn't go on this journey. Their parents didn't go on this journey. It was probably their great, great grandparents that did this journey. So there is some instinct there, some, you know, need to migrate. But we think that they use a combination of the angle of the sun. Probably their food is getting worse. The milkweeds that they're using are dying back, so there's probably some signal just from what they're eating. They may be using temperature and other weather cues that, you know, starting to feel like fall. So all of that kind of triggers that need to migrate. And what's really cool about that generation that grew up on that milkweed late in the summer is that instead of spending a lot of energy building reproductive organs, they focus more on building up fat reserves so they can make this really long journey. They will still eat as they go, but they need enough, to start out with, to make it, you know, actually, a lot of them don't make it because it's a really hard journey. So those are all the reasons why they start moving. And then, you know, how they navigate is a whole other mystery.

Mickenzee: Wow, that's so cool that there's so much still out there to learn. Okay, our next question is how do the monarchs know where to go? It's such a long journey.

Monarch butterflies huddled together on migration (photo by USFWS)

Emma: Yeah, I think in general we think that they are kind of driven to start flying south and depending on where they are in Canada and the United States, they might be going southwest, they might be going southeast. It kind of depends. They're probably using large topographic features like mountains. Right. And they're going to go to the path of least resistance. They're going to follow wind currents. They're not going to go over a mountain if they don't have to. So they're probably funneling down, rivers and again, like following the paths of mountains. And then in general, we think that they're probably using up the magnetic compass of the Earth. And then they're using visual cues as well. So all of that wind, magnets, sun, it's kind of amazing. And then once they actually get to where they're going. So they're kind of zeroing in on the parts of Mexico where they overwinter or coastal California, then how they really select, you know, which tree they're going to land on is another great mystery. And in general, at this point, we think that they are probably finding places where there are already other monarchs. But that very first monarch, why it picks where it picks, we see sometimes they land on the same branch of the same tree. And like, that feels a little bit like magic. And we don't quite understand how they know to go to that exact spot.

Mickenzee: Oh, that's so cool and exciting. Okay, so I think our questions get a little more complicated after this. This one is really interesting to me. Do monarchs think? And if so, what do they think about?

Monarch Butterfly sipping on nectar (photo by USFWS)

Emma: I loved this one when you sent it because I think the answer is yes, of course there is some kind of, you know, neural connection there. They have little insect brains. They're definitely thinking they're reacting to their environment. They can learn, you know, in experiments, which, colors or flower shapes are going to provide more food, more nectar. But are they thinking in the sense of, you know, being self-conscious and saying, I am a monarch? You know, I don't think we think animals, like, insects, have that amount of cognition. So I think it's probably more in the order of reacting, you know, to kind of what they're learning, building memories. And then, you know, they have these drives to reproduce, to migrate. And so there's probably some thinking in the sense about , that those actions.

Mickenzee: Very cool. Yeah. Oh, that's such a fun thought to think about too. Like, maybe when they're all clustered together in the tree, are they like, oh, is this so cozy? Or like, oh, hey, I remember you. We grew up on the same milkweed patch.

Emma: They're not social. And yet they have this like component that we view as like very social. Just kind of interesting.

Mickenzee: Our last question is a very sweet one. And it's do monarchs communicate with each other and do they help each other and support each other.

Monarch Caterpillar feast (photo by USFWS)

Emma: Yeah. No. Similar vein. You know, I think some of these are ideas. You know, we can't anthropomorphize or like we can't think about them like they're humans in the same way, but they definitely are communicating. It's a little different than us. They actually don't hear very well, and they make very minimal sounds. You could sometimes hear wing beats, but, so a lot of our verbal, you know, hearing communication that's not accessible to them. So they’re really using taste, smell, visual cues. They have big beautiful eyes if you look up close on a monarch with all these facets. So they're very visual creatures. So they are seeing each other and that's how they find mates. That's how a female, if she goes to lay an egg, may notice that there are other eggs or caterpillars on a single milkweed. And may choose to lay eggs elsewhere so they don't compete or accidentally get eaten. So they are communicating in that way. And definitely, you know, using their feet as their primary sources of, kind of tasting and smelling, their proboscis is a really fancy long butterfly tongue. So it's really different than what we think about. But I think their use of their eyes are very similar to how we, sense the world and thus communicate by seeing one another.

Mickenzee: Very cool. Yeah. It's so interesting to think about how all different animals view and sense the world in a completely different way than us.

Emma: And I didn't answer the second part of that question of just like how they help each other, and I was going to say, I think they do in the winter. And this is where the fact that they group together is not by chance. We think that they are grouping together. Which allows them in the spring and there's very few of them left to whoever has made it through this long migration, this hard winter. Then they have mates at the ready. So kind of similar to when we think about snakes or other animals getting together. It's kind of that allows the few that made it through to be close together, but they're probably also helping each other avoid predators, predators less likely to eat you. If you're with a whole bunch of other butterflies, your chances are lower. And so just that piece of it, is probably really important. And then there could be some amount, like penguins or something. We're really famous of, like how they regulate heat or, you know, termites or honeybee colonies. It's a little less understood and probably not as big of a factor, but there probably is some amount of like just physical protection to be in a group really clustered tightly together versus being out on your own from like a warmth perspective.

Mickenzee: Yeah. Yeah. It's by like grouping together and helping a community or kind of helping yourself too.

Emma: Totally

Mickenzee: Awesome. Well, thank you to the Lincoln third graders for asking your nature questions. And thanks, Emma, for coming on to teach us today.

Emma: Thanks so much for having me.

-----

If you're interested in learning more or getting involved with our programs, please head to our website swibirds.org and check out the free lessons, games and activities.

You can check out our insect lessons or Monarch Migration obstacle course. If you want to get outside with us, check out our events calendar for things like monarch tagging. If you have a big nature question of your own that you'd like to have answered, please have your teacher or a grown up submit your question to info@swibirds.org with the title questions for QuACK.

Make sure to include your grade in the school you attend so I can give you a shout out. Thanks for tuning in and I hope you join us next time on QuACK!

Check out SoWBA’s free lessons, games, and activities!

Get out and explore nature with us!

Make a donation to Southern Wisconsin Bird Alliance

Audio Editing and Transcription by Mickenzee Okon

Logo design by Carolyn Byers and Kaitlin Svabek

Music: “The Forest and the Trees” by Kevin MacLeod